Posts

-

A Gentle Introduction to Secure Computation

CommentsIn Fall 2015, I took CS 276, a graduate level introduction to theoretical cryptography. For the final project, I gave a short presentation on secure computation.

This blog post is adapted and expanded from my presentation notes. The formal proofs of security rely on a lot of background knowledge, but the core ideas are very clean, and I believe anyone interested in theoretical computer science can understand them.

What is Secure Computation?

In secure computation, each party has some private data. They would like to learn the answer to a question based off everyone’s data. In voting, this is the majority opinion. In an auction, this is the winning bid. However, they also want to maintain as much privacy as possible. Voters want to keep their votes secret, and bidders don’t want to publicize how much they’re willing to pay.

More formally, there are \(n\) parties, the \(i\)th party has input \(x_i\), and everyone wants to know \(f(x_1, x_2, \cdots, x_n)\) for some function \(f\). The guiding question of secure computation is this: when can we securely compute functions on private inputs without leaking information about those inputs?

This post will focus on the two party case, showing that every function is securely computable with the right computational assumptions.

Problem Setting

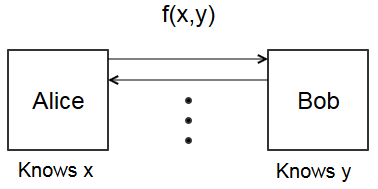

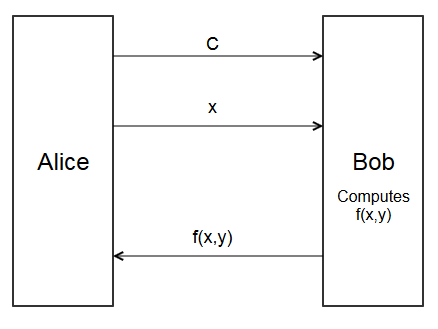

Following crypto tradition, Alice and Bob are two parties. Alice has private information \(x\), and Bob has private information \(y\). Function \(f(x,y)\) is a public function that both Alice and Bob want to know, but neither Alice nor Bob wants the other party to learn their input.

The classical example is Yao’s Millionaire Problem. Alice and Bob want to know who has more money. It’s socially unacceptable to brag about your wealth, so neither wants to say how much money they have. Let \(x\) be Alice’s wealth, and \(y\) be Bob’s wealth. Securely computing

\[f(x,y) = \begin{cases} \text{Alice} & \text{if } x > y \\ \text{Bob} & \text{if } x < y \\ \text{same} & \text{if } x = y \end{cases}\]lets Alice and Bob learn who is richer.

Before going any further, I should explain what security guarantees we’re aiming for. We’re going to make something secure against semi-honest adversaries, also known as honest-but-curious. In the semi-honest model, Alice and Bob never lie, following the specified protocol exactly. However, after the protocol, Alice and Bob will analyze the messages received to try to extract information about the other person’s input.

Assuming neither party lies is naive and doesn’t give a lot of security in real life. However, it’s still difficult to build a protocol that leaks no unnecessary information, even in this easier setting. Often, semi-honest protocols form a stepping stone towards the malicious case, where parties can lie. Explaining protocols that work for malicious adversaries is outside the scope of this post.

Informal Definitions

To prove a protocol is secure, we first need to define what security means. What makes secure computation hard is that Alice and Bob cannot trust each other. Every message can be analyzed for information later, so they have to be very careful in what they choose to send to one another.

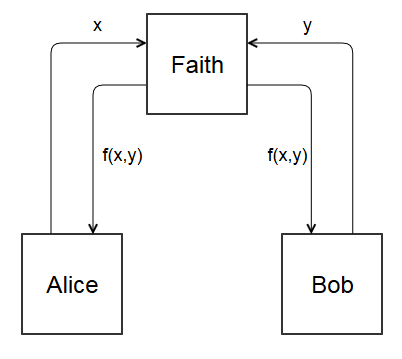

Let’s make the problem easier. Suppose there was a trusted third party named Faith. With Faith, Alice and Bob could compute \(f(x,y)\) without directly communicating.

- Alice sends \(x\) to Faith

- Bob sends \(y\) to Faith

- Faith computes \(f(x,y)\) and sends the result back to Alice and Bob

This is called the ideal world, because it represents the best case scenario. All communication goes through Faith, who never reveals the input she received. She only replies with what the parties want to know, \(f(x,y)\).

If this is the best case scenario, we should define security by how close we get to that best case. This gives the following.

A protocol between Alice and Bob is secure if it is as secure as the ideal world protocol between Alice, Bob, and Faith.

To make this more precise, we need to analyze the ideal world’s security.

Suppose we securely computed \(f(x,y) = x+y\) in the ideal world. At the end of communication, Alice knows \(x\) and \(x+y\), while Bob knows \(y\) and \(x + y\). If Alice computes

\[(x+y) - x\]she learns Bob’s input \(y\). Similarly, if Bob computes

\[(x+y) - y\]he learns Alice’s input \(x\). Even the ideal world can leak information. In an extreme case like this, possibly even the entire input! If Alice and Bob want to know \(f(x,y) = x + y\), they have to give up any hope of privacy.

This is an extreme example, but most functions leak something about each party. Going back to the millionaire’s problem, suppose Alice has \(10\) dollars and Bob has \(8\) dollars. They securely compute who has the most money, and learn Alice is richer. At this point,

- Alice knows Bob has less than \(10\) dollars because she’s richer.

- Bob knows Alice has more than \(8\) dollars because he’s poorer.

However, there is still some privacy: neither knows the exact wealth of the other.

Since \(f(x,y)\) must be given to Alice and Bob, the best we can do is learn nothing more than what was learnable from \(f(x,y)\). This gives the final definition.1

A protocol between Alice and Bob is secure if Alice learns only information computable from \(x\) and \(f(x,y)\), and Bob learns only information computable from \(y\) and \(f(x,y)\)

(Side note: if you’ve seen zero-knowledge proofs, you can alternatively think of a protocol as secure if it is simulatable from \(x, f(x,y)\) for Alice and \(y, f(x,y)\) for Bob. In fact, this is how you would formally prove security. If you haven’t seen zero-knowledge proofs, don’t worry, they won’t show up in later sections, and we’ll argue security informally.)

Armed with a security definition, we can start constructing the protocol. Before doing so, we’ll need a few cryptographic assumptions.

Cryptographic Primitives

All of theoretical cryptography rests on assuming some problems are harder than other problems. These problems form the cryptographic primitives, which can be used for constructing protocols.

For example, one cryptographic primitive is the one-way function. Abbreviated OWF, these functions are easy to compute, but hard to invert, where easy means “doable in polynomial time” and hard means “not doable in polynomial time.” Assuming OWFs exist, we can create secure encryption, pseudorandom number generators, and many other useful things.

No one has proved one-way functions exist, because proving that would prove \(P \neq NP\), and that’s, well, a really hard problem, to put it mildly. However, there are several functions that people believe to be one-way, which can be used in practice.

For secure computation, we need two primitives: oblivious transfer, and symmetric encryption.

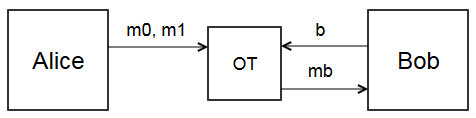

Oblivious Transfer

Oblivious transfer (abbreviated OT) is a special case of secure computation. Alice has two messages \(m_0, m_1\). Bob has a bit \(b\). We treat oblivious transfer as a black box method where

- Alice gives \(m_0, m_1\)

- Bob gives bit \(b\), \(0\) or \(1\)

- If \(b = 0\), Bob gets \(m_0\). Otherwise, he gets \(m_1\). In both cases, Bob does not learn the other message.

- Alice does not learn which message Bob received. She only knows Bob got one of them.

You can think of the OT box as a trusted third party, like Faith. Letting Alice send messages without knowing which message was received will be key to the secure computation protocol. I don’t want to get into the details of implementing OT with only Alice and Bob, since they aren’t that interesting. If you’re curious, Wikipedia has a good example based on RSA.

Symmetric Encryption

Symmetric encryption allows two people to send encrypted messages that cannot be decrypted without the secret key. Formally, a symmetric encryption scheme is a pair of functions, encrypter \(E\) and decrypter \(D\), such that

- \(E_k(m)\) is the encryption of message \(m\) with key \(k\).

- \(D_k(c)\) is the decryption of ciphertext \(c\) with key \(k\).

- Decrypting with the same secret key gives the original message, or \(D_k(E_k(m)) = m\),

- Given just ciphertext \(c\), it is hard to find a key \(k\) and message \(m\) such that \(E_k(m) = c\). (Where again, hard means not solvable in polynomial time.)

The above is part of the standard definition for symmetric encryption. For the proof, we’ll need one more property that’s less conventional.

- Decrypting \(E_k(m)\) with a different key \(k'\) results in an error.

With all that out of the way, we can finally start talking about the protocol itself.

Yao’s Garbled Circuits

Secure computation was first formally studied by Andrew Yao in the early 1980s. His introductory paper demonstrated protocols for a few examples, but did not prove every function was securely computable. That didn’t happen until 1986, with the construction of Yao’s garbled circuits.

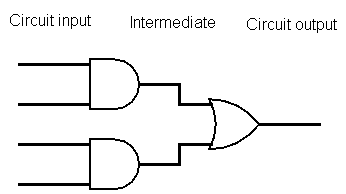

To prove every function was securely computable, Yao proved every circuit was securely computable. Every function can be converted to an equivalent circuit, and we’ll see that working in the circuit model of computation makes the construction simpler.

A Quick Circuit Primer

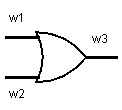

For any function \(f(x,y)\), there is some circuit \(C\) such that \(C(x,y)\) gives the same output. That circuit \(C\) is made up of logic gates and wires connecting them. Each logic gate has two input wires and one output wire, and computes a simple Boolean function, like AND or OR.

The wires in a circuit can be divided into three categories: inputs for the circuit, outputs for the circuit, and intermediate wires between gates.

Garbling Circuits

Here is a very obviously insecure protocol for computing \(f(x,y)\)

- Alice sends circuit \(C\) to Bob.

- Alice sends her input \(x\) to Bob.

- Bob evaluates the circuit to get \(f(x,y)\)

- Bob sends \(f(x,y)\) back to Alice.

This works, but Alice has to send \(x\) to Bob.

This is where garbling comes in. Instead of sending \(C\), Alice will send a garbled circuit \(G(C)\). Instead of sending \(x\), she’ll send \(x\) encoded in a certain way. It will be done such that Bob can evaluate \(G(C)\) with Alice’s encoded input, without learning what Alice’s original input \(x\) was, and without exposing any wire values except for the final output.2

Number the wires of the circuit as \(w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_n\). For each wire \(w_i\), generate two random encryption keys \(k_{i,0}\) and \(k_{i,1}\). These will represent \(0\) and \(1\).

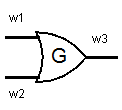

A garbled circuit is made of garbled logic gates. Garbled gates act the same as regular logic gates, except they operate on the sampled encryption keys instead of bits.

Suppose we want to garble an OR gate. It has input wires \(w_1,w_2\), and output wire \(w_3\).

Internally, an OR gate is implemented with transistors. However, at our level of abstraction we treat the OR gate as a black box. The only thing we care about is that it follows this behavior.

- Given \(w_1 = 0, w_2 = 0\), it sets \(w_3 = 0\).

- Given \(w_1 = 0, w_2 = 1\), it sets \(w_3 = 1\).

- Given \(w_1 = 1, w_2 = 0\), it sets \(w_3 = 1\).

- Given \(w_1 = 1, w_2 = 1\), it sets \(w_3 = 1\).

This is summarized in the function table below.

\[\begin{array}{ccc} w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{array}\]A garbled OR gate goes one step further.

It instead takes \(k_{1,0}, k_{1,1}\) for \(w_1\), and \(k_{2,0}, k_{2,1}\) for \(w_2\). Treating these keys as bits \(0\) or \(1\), the output is \(k_{3,0}\) or \(k_{3,1}\), depending on which bit the gate is supposed to return. You can think of it as replacing the OR gate with a black box that acts as follows.

- Given \(w_1 = k_{1,0}, w_2 = k_{2,0}\), it sets \(w_3 = k_{3,0}\).

- Given \(w_1 = k_{1,0}, w_2 = k_{2,1}\), it sets \(w_3 = k_{3,1}\).

- Given \(w_1 = k_{1,1}, w_2 = k_{2,0}\), it sets \(w_3 = k_{3,1}\).

- Given \(w_1 = k_{1,1}, w_2 = k_{2,1}\), it sets \(w_3 = k_{3,1}\).

By replacing every logic gate with a garbled gate, we can evaluate the circuit using random encryption keys instead of bits.

We implement this using symmetric encryption. For every possible pair of input keys, the correct output is encrypted using both those keys. Doing this for all possible inputs gives the garbled table,

\[\begin{array}{c} E_{k_{1,0}}(E_{k_{2,0}}(k_{3,0})) \\ E_{k_{1,0}}(E_{k_{2,1}}(k_{3,1})) \\ E_{k_{1,1}}(E_{k_{2,0}}(k_{3,1})) \\ E_{k_{1,1}}(E_{k_{2,1}}(k_{3,1})) \end{array}\]With one secret key for each wire, Bob can get the correct output by attempting to decrypt all 4 values. Suppose Bob has \(k_{1,0}\) and \(k_{2,1}\). Bob first decrypts with \(k_{1,0}\). He’ll decrypt exactly two values, and will get an error on the other two.

\[\begin{array}{c} E_{k_{2,0}}(k_{3,0}) \\ E_{k_{2,1}}(k_{3,1}) \\ \text{error} \\ \text{error} \end{array}\]Decrypting the two remaining messages with \(k_{2,1}\) gives

\[\begin{array}{c} \text{error} \\ k_{3,1} \\ \text{error} \\ \text{error} \end{array}\]getting the key corresponding to output bit \(1\) for wire \(w_3\).

(To be fully correct, we also shuffle the garbled table, to make sure the position of the decrypted message doesn’t leak anything.)

Creating the garbled table for every logic gate in the circuit gives the garbled circuit. Informally, here’s why the garbled circuit can be evaluated securely.

- For a given garbled gate, Bob cannot read any value in the garbled table unless he has a secret key for each input wire, because the values are encrypted.

- Starting with the keys for the circuit input, Bob can evaluate the garbled gates in turn. Each garbled gate returns exactly one key, and that key represents exactly the correct output bit. When Bob gets to the output wires, he must get the same output as the original circuit.

- Both \(k_{i,0}\) and \(k_{i,1}\) are generated randomly. Given just one of them, Bob has no way to tell whether the key he has represents \(0\) or \(1\). (Alice knows, but Alice isn’t the one evaluating the circuit.)

Thus, from Bob’s perspective, he’s evaluating the circuit by passing gibberish as input, propagating gibberish through the garbled gates, and getting gibberish out. He’s still doing the computation - he just has no idea what bits he’s actually looking at.

(The one minor detail left is key generation for the output wires of the circuit. Instead of generating random keys, Alice uses the raw bit \(0\) or \(1\), since Alice needs Bob to learn the circuit output.)

The Last Step

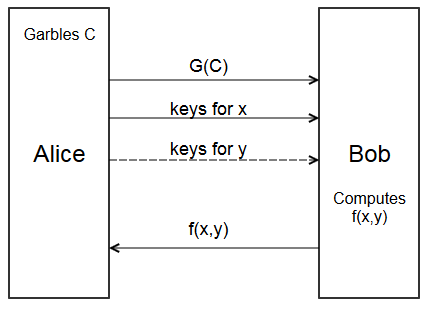

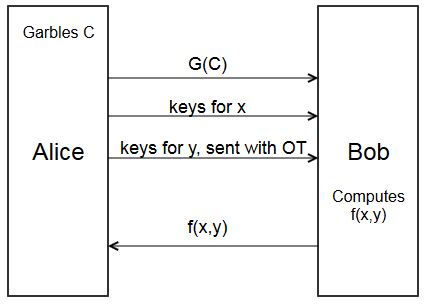

Here’s the new protocol, with garbled circuits

- Alice garbles circuit \(C\) to get garbled circuit \(G(C)\)

- Alice sends \(G(C)\) to Bob.

- Alice sends the keys for her input \(x\) to Bob.

- Bob combines them with the input keys for \(y\), and evaluates \(G(C)\) to get \(f(x,y)\)

- Bob sends \(f(x,y)\) back to Alice.

There’s still a problem. How does Bob get the input keys for \(y\)? Only Alice knows the keys created for each wire. Bob could give Alice his input \(y\) to get the right keys, but then Alice would learn \(y\).

One solution is to have Alice send both keys for each of \(y\)’s input wires to Bob. For each wire, Bob can then pick the key corresponding to the correct bit of \(y\). That way, Bob doesn’t have to give Alice \(y\), but can still run the circuit.

However, this has a subtle bug: by giving Bob both keys for his input wires, Alice lets Bob run the circuit with an arbitrary \(y\). Letting Bob evaluate \(f(x,y)\) many times gives Bob more information. Going back to the millionaire’s problem, let \(x = 10\) and \(y = 8\). At the end, Bob learns Alice is richer, meaning \(x > 8\). But, if he later evaluates \(f(x, 9)\), he’ll learn \(x > 9\), which is more than he should know.

Thus, to be secure, Bob should only get to run the circuit on exactly \(x,y\). To do so, he needs to get the keys for \(y\), and only the keys for \(y\), without Alice learning which keys he wants. If only there was a way for Alice to obliviously transfer those keys…

Alright, yes, that’s why we need oblivious transfer. Using oblivious transfer to fill in the gap, we get the final protocol.

- Alice garbles circuit \(C\) to get garbled circuit \(G(C)\)

- Alice sends \(G(C)\) to Bob.

- Alice sends the keys for her input \(x\) to Bob.

- Using oblivious transfer, for each of Bob’s input wires, Alice sends \(k_{i,y_i}\) to Bob.

- With all input keys, Bob can evaluate the circuit to get \(f(x,y)\)

- Bob sends \(f(x,y)\) back to Alice.

This lets Alice and Bob compute \(f(x,y)\) without leaking their information, and without trusted third parties.

Conclusion

This protocol is mostly a theoretical exercise. However, there has been recent work to make it fast enough for practical use. It’s still tricky to use, because the desired function needs to be converted into an equivalent circuit.

Despite this difficulty, Yao’s garbled circuits are still a very important foundational result. In a post-Snowden world, interest in cryptography is very high. There’s lots of use in designing protocols with decentralized trust, from Bitcoin to secure cloud storage. It’s all very interesting, and I’m sure something cool is just around the corner.

Thanks to the many who gave comments on drafts of this post.

Footnotes

-

By “information computable”, we mean “information computable in polynomial time”. ↩

-

There’s a very subtle point I’m glossing over here. When \(f(x,y)\) is converted to a circuit \(C\), the number of input wires is fixed. To create an equivalent circuit, Alice and Bob need to share their input lengths. For a long time, this was seen as inevitable, but it turns out it’s not. When I asked a Berkeley professor about this, he pointed me to a recent paper (2012) showing input length can be hidden. I haven’t read it yet, so for now assume this is fine. ↩

-

Go: More Complicated Than Go Fish

CommentsAs something “hot off the presses” (hot off the keyboard?), this is a bit unpolished.

Yesterday, Google DeepMind announced they had developed an AI called AlphaGo that reached expert level in Go, beating the European Go champion.

It got picked up by, well, everybody. I don’t want to catalog every article, so here’s a sample: MIT Technology Review, Wired, Ars Technica, and The New York Times. Posts from friends and famous AI researchers have been filling my news feed, and it’s all along the lines of “Well done” or “Holy shit” or “I for one welcome our new robot overlords.”

Although computer Go isn’t one of my main interests, Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is. The biggest application of MCTS is in computer Go, and when you spend two semesters researching MCTS, you end up reading a few computer Go papers along the way. So, I figure my perspective is at least slightly interesting.

Prior Work

My first reaction was that AlphaGo was very impressive, but not surprising.

This is at odds with some of the reporting. The original blog post says that

Experts predicted it would be at least another 10 years until a computer could beat one of the world’s elite group of Go professionals.

The MIT Technology Review repeats this with

Google’s AI Masters the Game of Go a Decade Earlier Than Expected

Wired has an actual quote by said expert, Rémi Coulom.

In early 2014, Coulom’s Go-playing program, Crazystone, challenged grandmaster Norimoto Yoda at a tournament in Japan. And it won. But the win came with caveat: the machine had a four-move head start, a significant advantage. At the time, Coulom predicted that it would be another 10 years before machines beat the best players without a head start.

I entirely understand why it sounds like this result came out of nowhere, but it didn’t. Giant leaps are very rare in research. For problems like computer Go, it’s more like trying to punch through a thick wall. At first, the problem is unapproachable. Over the years, people make incremental progress, chipping away bit by bit, building prototype chisels, exploring blueprints for hypothetical pile drivers, and so on. Eventually, all the right ideas collect by the wall, some group puts the pieces together in the right way, and finally breaks down the wall.

Then reporters only talks about the final breakthrough, and it sounds like complete magic to outsiders.

This isn’t a dig at science reporting. You have to be steeped in a research field to see the signs of a breakthrough, and asking reporters to do that for every field is unreasonable. Even then, people close to breakthroughs are often wrong. I’m sure there are plenty of professors who were (and maybe still are) pessimistic on neural nets and optimistic on SAT solvers. It’s also often in the interest of authors to play up the strengths of their research for articles.

Back to Go. I wasn’t surprised because DeepMind released a preprint of their previous Go paper on December 2014. (Incidentally, Clark and Storkey released a similar paper 10 days before them, with worse results. The day before Google announced AlphaGo, Facebook AI Research updated a preprint for their computer Go work. Funny how that goes.)

Before this paper, the best approach was Monte Carlo Tree Search. In MCTS, the algorithm evaluates board positions by playing many random games, or rollouts. Using previous outcomes, it focuses the search on more promising moves. Progress in MCTS strategies came from tweaking the rollout policy. A stronger rollout player gives more accurate results, but because MCTS runs hundreds of thousands of rollouts, even small increases in computing cost get magnified.

What made DeepMind’s first paper so impressive was that it achieved good performance with zero search. Pass in the board, get a move in a few milliseconds. Compared to the 5 second search time other programs used, this was radically different. It didn’t beat existing bots, but it didn’t have to.

The approach was simple. Using supervised learning, they trained a convolutional neural net to predict the next move from a database of expert level games. With a big enough CNN, they got to 55.2% accuracy, which beat all prior move predictors.

At the end of their 2014 paper, there’s a short section on combining their CNN with search. They didn’t get very far, besides showing it was an obviously good idea if it could be made computationally feasible. Ever since that paper, it’s felt like the last thing computer Go needed was a combination of heavy duty neural net move predictors with MCTS, done such that computation time didn’t explode.

With AlphaGo, that’s finally happened. So no, these results aren’t that crazy. There was a clear roadmap of what needed to happen, and people figured it out.

To be fair to Rémi Coulom, his quoted remarks came before DeepMind’s preprint was sent to the computer-go mailing list. I’m sure he’s been following this closely, and it’s an unfortunate citation without context.

The New Stuff

I know I’ve been a bit down on AlphaGo, but I don’t want that to fool anybody. AlphaGo is exceptionally impressive. If you have access, I highly recommend reading the Nature paper on your own. It’s very well written, and the key ideas are conveyed well.

If you don’t have access, here’s the quick summary.

- Using the supervised dataset of expert level games. they train two networks. One is a small rollout network, used for rollouts in the MCTS. The other is a large CNN, similar to the Dec 2014 paper. This is called the policy network.

- The policy network is further refined through self-play and reinforcement learning. (The paper calls this the RL policy network.)

- Finally, they train a value network, which predicts the value of a board

if both players play according to the RL policy network.

- The value network gives an approximation of rollout values with the larger network, which is too expensive to do during real life play. It’s an approximation, but it’s thousands of times faster.

The first part that piqued my interest was how many networks were trained for AlphaGo. It makes sense: different tasks in MCTS are better suited to different network architectures, so you might as well use a different neural net for each one.

However, I found this side remark much more interesting.

Using no search at all, the RL policy network won 85% of games against Pachi, [the strongest open source Go program]. In comparison, the previous state-of-the-art, based only on supervised learning of convolutional networks, won 11% of games against Pachi and 12% against a slightly weaker program, Fuego.

Before reading the paper, I thought all the improved performance came from just search. The reality is much more exciting, because it suggests there’s still a gap we’re failing to acheive for CNN-based agents. Furthermore, we can bridge this gap by bootstrapping from the supervised data to unsupervised self-play data.

Let me repeat that: this paper shows that when labelled data is lacking something about the problem, we can still learn from unlabeled data.

This is huge. This is the kind of thing that makes people want to do research.

The one dream of anybody in ML is unsupervised learning. It’s very hard, but it’s so much cooler when it works, and the potential of unsupervised learning feels unbounded. Supervised learning will always be held back in part by whether there’s a large enough labeled dataset to capture all the information for a problem. Labels need to be provided by humans, so constructing large datasets takes a lot of manpower.

By contrast, unsupervised learning is held back only by the sheer difficulty of learning when you don’t know what the answer is supposed to be. This is an idea problem, not a dataset problem. It’s easy to get more unsupervised data; just look around the world more!

The AlphaGo paper doesn’t do unsupervised learning, but it’s a big step towards that direction, and using supervised learning to pre-train unsupervised learning sounds like a good idea anyways. If you look at the results table, the final policy network (the one before self-play refinement) got 55.4% move prediction accuracy, compared to 55.2% move accuracy from the December 2014 paper. The improved performance doesn’t come from a better supervised CNN, it all comes from self-play. Remember that the 85% win rate against Pachi doesn’t even use search. I’m sure plenty of people are investigating whether a similar approach works on problems besides Go.

Compared to this, interfacing the neural net with search feels less important. There are some neat ideas here: train a special small network for rollouts, pre-seed initial value estimates with the heavy-duty net (which you can afford because you only need it once per node), and combine the approximate value from the policy network with the true value from the weaker rollout network. From an engineering perspective, they’re doing a crazy asynchronous CPU + GPU architecture that sounds like a nightmare to manage. There are plenty of ideas here, but to me the story is proving the capability of unsupervised learning.

Final Caveats

I’ll close with the few downsides I see on skimming the paper.

- This still uses a lot of computation time. When they announced results for running AlphaGo on one machine, they mean a machine with 48 CPUs and 8 GPUs. The version used against the European Go champion Fan Hui runs on a distributed cluster of 1202 CPUs and 176 GPUs. Let’s just say this is out of the reach of the average enthusiast and move on.

- The reported 5-0 record against Fan Hui was in formal games, one game per day. Each day, Fan also played an informal game, with shorter time controls. In those games, AlphaGo won 3-2.

-

This takes a lot of training time. From the methods section:

Updates were applied asynchronously on 50 GPUs using DistBelief […] Training [for the supervised network] took around 3 weeks for 340 million training steps.

Then, for self-play refinement,

The [RL policy] network was trained in this way for 10,000 mini-batches of 128 games, using 50 GPUs for one day.

And finally, for the value network,

The value network was trained for 50 million mini-batches of 32 positions, using 50 GPUs, for one week.

That adds up to a month, even on 50 GPUs. So, for anyone looking to try something similar, make sure to use a small problem, and keep a computing cluster handy.

-

Mystery Hunt 2016 Wrap-Up

CommentsTargeted towards people who did MIT Mystery Hunt 2016. I doubt you’ll care about this if you didn’t participate. Some spoilers.

Here’s the thing about puzzle hunts: they bring together the strangest people. Strange in a good way. The biggest reason puzzles are awesome is because they provide concentrated bursts of problem solving euphoria, but only the slightly unhinged are willing to destroy their sleep schedules by working on puzzles for 3 days straight. Still, any week where I get to hear proposals for sneakernet from space to Earth is pretty awesome.

Normally, I hunt on bigger teams because they have better remote solver support. Because I went in-person this year, I decided I should try out a smaller team, so I hunted with ET Phone In Answer. It was definitely a different dynamic. In my previous Hunts, it felt like I wasn’t a big contributor. (For context, my first Hunt was with Sages.) When 10 people are looking at the same puzzle, the math means it’s unlikely you find the a-ha, because there’s so many other people working on it. On the other hand, I do like finishing Hunt, and that’s a lot easier on larger teams. Something I’ll need to think about for next year.

Thanks to sponsors, at the start of this Hunt every team got Google Cardboard, Fitbit notebooks, and Fitbit pens. In a true display of Mystery Hunt paranoia, the first thing we did was open the notebooks and disassemble a pen to verify none of them were puzzles. I blame the first aid kit puzzle from the Alice hunt.

After kickoff, my first puzzle of the Hunt was You Complete Me. We got the correct coefficients after some staring, but it took us a while to get the next square a-ha. Once we did, we got stuck on extraction and abandoned it. The next day, someone looked at it, did the obvious thing, and solved it in five minutes. In hindsight, I have no idea how we missed it.

Had fun finding the answer to Pictocryptolists. As with all substitution ciphers, it took a while to get the first foothold, but once we got the theme it came together like clockwork. Around five people cycled through it. It was straightforward but tediuos, which made it a great cooldown puzzle if you were frustrated at your current puzzle.

Oh, for once I identified a meta mechanism! It was for Obedience Training. We were very confident in ????PROOF BREEDERS, where exactly two of the ? were consonants, but it took us until Sunday to guess the correct starting word. (It was GOOFPROOF, for what it’s worth. I know it’s on theme, but FOOLPROOF makes so much sense…)

Meet the Loremipsumstanis was frustrating. Everyone collected data for it once we knew how the Bacon Ipsum worked, because it was too much fun to justify working on anything else. It was all smooth sailing, until we got to the final cryptic phrase. We knew the answer had to be eight letters long from both the given numbers and the Rip Van Winkle meta constraint, but we just couldn’t get it, and the puzzle stayed unsolved for all of Hunt. I’m still so disappointed TONY HAWK wasn’t correct.

I finally found a use for my knowledge of Knuth up-arrow notation! …Well, I would have, if I hadn’t looked at Identify, SORT, Index, Solve five hours after it was solved. As a fan of incredibly large numbers, I’m sad I missed it. Any puzzle involving Busy Beavers and Ackermann functions is automatically awesome. Based on the Mystery Hunt subreddit, other people liked it too, so hopefully I’ll get another chance to reason about exponent towers.

Now, a slight digression. A ton of puzzles came out between Saturday night and Sunday morning, but I didn’t work on them. Instead, I was doing Round 1 of Facebook Hacker Cup. Take it from me, don’t start a programming competition at 2 AM after doing puzzles all day. I briefly looked at the problems, and decided to focus on the first 3. I did very minimal testing, submitting my last solution 5 seconds before the contest ended. Miraculously, they were all correct. I expect to die in Round 2, and will be very surprised if I make top 500 for the T-shirt, but at least I made it.

Back to puzzles! Shortly after coming into HQ, somebody called out “Ponies!”. I’ve always felt like Mystery Hunt had to have an My Little Pony puzzle at some point, and this year someone on the writing team felt the same way. We solved it in around forty minutes, seamlessly going from data collection to a-ha to extraction. On point construction, clean theming, and solvable without MLP knowledge but much faster with it. My second most enjoyable solve of the Hunt.

But, my favorite solve of the Hunt has to go to Sleeping Beauty meta. I didn’t know Nikoli created a logic puzzle with no numbers, but now I do. Other people did the legwork of filling in the grid and solving with incomplete info, but we didn’t know what to do with the logic puzzle solution. We abandoned it Sunday morning. Around twenty-five minutes before Hunt HQ closed, I gave a final look, and figured it out. I didn’t actually do that much, but it feels really good to be the guy (or gal) to figure out the final extraction, especially on a metapuzzle.

We weren’t close to finishing, but I never expected to finish, so that was fine. I’m very curious to see what kind of hunt Setec will make. After seeing Sneakers, I’ll say only this: Setec can have Too Many Secrets, as long as they don’t have Too Many Puzzles.

Finally, for tradition’s sake: this post is not a puzzle.

(Just kidding, it is. Yes, really. I promise it’s short. If something seems sketchy, look at the remainder. You’ll need more numbers to get the answer, and here they are: -10, 5, -10, -3, 9, -1, -3.)

The answer is DREAMER.

This is a barebones identify, sort, index, solve puzzle. Not very interesting, but it gets the job done, and I didn't want to make something too complicated. There are 7 given numbers, and 7 puzzles are linked. Furthermore, sometimes the post spells out numbers and sometimes it doesn't. The comment that you'll need more numbers should also sound fishy. If you read carefully, every paragraph linking a puzzle has exactly one number spelled out in words. Every other paragraph uses digits. The numbers are five, five, two, eight, five, forty, and twenty-five. Index the number into each of those paragraphs to get the clue phrase PUZZLE ANSWER FOR DATA USE SAME NUMBERS From the links, look up the answer to each puzzle. As clued, use the same paragraph numbers to index into the puzzle answers. Some numbers won't work, but the comment to "look at the remainder" should hopefully lead you to reducing the number if the answer is too short. Doing so gives NMODDFU and shifting by the final numbers gives DREAMER as the answer.