Posts

-

How Pokemon Go Can Teach Us About Social Equality

CommentsI’ve been playing Pokemon Go. If you haven’t played the game, here’s all you need to know for this post.

- You play as a Pokemon trainer. Your goal is to catch Pokemon. Doing so gives you resources you can spend to power up your Pokemon. Catching Pokemon also increases your trainer level, which increases the power of Pokemon you find in the wild.

- At level 5, players declare themselves as Team Mystic, Team Valor, or Team Instinct, which are blue, red, and yellow respectively.

- Your goal is to claim gyms for your team and defend them from enemy teams. Gyms are real world landmarks you can claim for your team if you’re within range of them. Once claimed, players can either train gyms their team owns to make them harder to defeat, or fight enemy gyms to claim them for their own team. Both are easier if your Pokemon have higher CP (Combat Power).

In my region, Mystic has the most members, followed by Valor, followed by Instinct. I chose Team Instinct, because come on, Zapdos is awesome. Unfortunately, because Instinct has so few members, it’s the butt of many jokes.

There are a few gyms in walking distance of where I live, but they’re perpetually owned by Team Mystic. My strongest Pokemon is a 800 CP Arcanine, and when the gym is guarded by a 1700 CP Vaporeon, there’s no point even trying.

However, on exactly one occasion, the gym near my house was taken over by Team Instinct. Other Instinct players trained it to hell and back. The weakest Pokemon protecting it had over 2000 CP, and the strongest was a 2700 CP Snorlax. Eventually, some Mystic players took it down, but for just over a day I had hope that Instinct players could make it after all.

Okay. What does that story have to do with social equality?

***

To explain myself, I’m going to jump back to a more serious turf war: World War 2.

The United States was interested in minimizing planes lost during bombing runs. To that end, they hired several academics to study aircraft flown in previous missions. Initially, the study concluded that the regions that suffered the most damage should be reinforced with armor.

Then, the statistician Abraham Wald had a moment of insight. The aircraft studied were aircraft that survived their missions. That meant the damaged areas were actually the least important parts of the aircraft, because the pilot was able to land the plane safely. He recommended adding armor to the regions with no damage instead.

This is known as survivorship bias. It’s not enough to analyze just the population we observe. We also need to consider what happened to the population we aren’t able to observe.

Applying this to Pokemon Go is easy enough. Let’s assume that team choice doesn’t affect the strength of the player. This is a safe assumption, because the fastest ways to level up are catching Pokemon, visiting Pokestops, and evolving Pokemon, all of which can be done no matter what team you’re on. Given this, gyms owned by Team Instinct face the most adversity, because they can be attacked by both Team Mystic and Team Valor, the two largest teams. So, given that I got to observe a Team Instinct gym, it must be stronger than a similar Mystic or Valor gym. Otherwise, it wouldn’t have lasted long enough for me to observe.

Conclusion: Instinct gyms are badass.

Applying vaguely anthropic arguments to Pokemon Go is fun and all, but survivorship bias has more important applications. Implicit discrimination in the workplace, for example. Suppose you’re Hispanic, and want to work in the software industry. A company releases a study showing their Hispanic employees outperform their colleagues. This is actually a bad sign. If a company is implicitly biased against Hispanics in their hiring process, the average Hispanic programmer they hire will outperform their other hires, because they have to survive a tougher hiring process.

This isn’t a new idea. Paul Graham wrote an essay on the exact same point, noting this was a litmus test people could check at their own companies. What makes this argument nice is that it applies no matter what the job market looks like. If a company doesn’t have many female engineers, they can claim it’s a pipeline problem and there aren’t enough women in the programming workforce. But, if their female engineers consistently outperform their other engineers, they’re likely biasing in the hiring process. To quote Paul Graham’s essay,

This is not just a heuristic for detecting bias. It’s what bias means.

It’s incredibly important to understand these arguments, because they fly in the face of intuition. If a person says some of the smartest people they know are black…well, for one, even saying something like that is a red flag. But also, it could mean that they’re only willing to be friends with those people because they’re so smart.

***

To be fair, there are a ton of confounding factors that muddle these claims. In Pokemon Go, although Mystic gyms don’t need to be strong to survive, they often become strong anyway, because fewer people attack them and more people can train them. In the software industry, there are strong socioeconomic feedback loops that help perpetuate the current demographic imbalance. If a company notices that rich employees perform better than poor ones, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re prejudiced against rich people.

Survivorship bias is not an end-all argument. It’s simply one more filter to protect yourself from making the wrong conclusion. Otherwise, you don’t protect airplanes properly, or you don’t recognize discrimination when you should.

As for Pokemon Go? Well, honestly, there are more important problems in the world than the troubles of Team Instinct. I’m sure we’ll find ways to deal with it.

-

The Machine Learning Casino

CommentsMachine learning is the study of algorithms that let a computer learn insights from data in a semi-autonomous way.

Machine learning research sounds like a process where you get to think really hard about how to improve the ways computers learn those insights.

Machine learning research is actually a process that takes over your life, by tricking you into gambling your time into implementing whatever heuristic seem most promising. Then you get to watch it fail in the most incomprehensible ways imaginable.

***

Despite its foundations in statistics, ML is mostly an experimental science.

That’s not saying there’s no theory. There’s plenty of theory. Bandit problems, convex and non-convex optimization, graphical models, and information theory, to name a few areas. The proofs are there, if you look for them.

I’m also not saying there’s no place for theory. Not everyone wants to spend the time to learn why their algorithm is guaranteed to converge, but everyone wants the proof to exist.

However, in the applications-driven domains that drive AI hype, people care about results first, theoretical justification second. That means a lot of heuristics. Often, those heuristics are bound together in an unsatisfying way that works empirically, but has very little founding theoretically.

How do we discover those heuristics? Well, by the scientific method.

- Make hypothesis.

- Design an experiment to test that hypothesis.

- Run the experiment and interpret the results.

- Refine the hypothesis with more informed experiment designs.

- Repeat until enlightenment.

In machine learning, hypotheses are promising algorithms, and experiments are benchmarks of those algorithms.

Hey, what’s the issue? Just run experiments, until something works!

Well, gather round. I’ve got a whole plate of beef to share, with plenty of salt.

***

Current state of the art methods are both probabilistic and incredibly customizable. Empirically, probabilistic approaches work well on large datasets, and datasets are very very large these days.

Their customizability means there’s an endless number of variations you can try. Have you tried tweaking your hyperparameters? Whitening your data? Using a different optimization algorithm? Making your model simpler? Making your model more complex? Using batch norm? Changing your nonlinearity? The dream is that we discover an approach whose average case is good enough to work out of the box. Unfortunately, we aren’t there yet. Neural nets are magical, but they’re still quite finicky once you move past simple problems.

Standard practice in ML is to publish a few good settings, and none of the settings that failed. This would be insane in other fields, but in ML, it’s just how things are. And sometimes, the exact same settings don’t even work! You’d think we could do better, given that the field is pure software, but failure to replicate is still a real issue.

This is the most infuriating part of ML, for anyone who appreciates the beauty of mathematical proofs. There’s no theoretical motivation behind hyperparameter tuning. It’s just something you have to do. The beauty of an ML idea is uncorrelated with its real-world performance. Here’s a conversation I overheard once, between a computer vision professor and one of his students.

Student: It doesn’t work.

Professor: No! It doesn’t work? The theory’s too beautiful for it not to work!

Student: I know. The argument is very elegant, but it doesn’t work in practice. Not even on Lenna.

Professor: (in a half-joking tone) Maybe if we run it on a million images, in parallel, it’ll magically start working.

Student: If it doesn’t work on a single image of Lenna, it’s not going to work on a million copies of Lenna.

Professor: Ahhhh, I suppose so. What a shame.

I feel their pain.

After training enough machine learning models, you gain an intuition for which knobs are most important to turn, and can diagnose the common failure modes. Your ad hoc explanations start condensing into a general understanding of when approaches are likely to work. However, this understanding never quite hits the level of guaranteed success. I like to joke that one day, the theorists will catch up and recommend an approach for reasons better than “it works empirically”, but I don’t think it’ll happen anytime soon. The theory is very hard.

(What theory has done is produce the no free lunch theorem. Informally, it says that no algorithm can beat another algorithm on every possible problem. In other words, there will never be One Algorithm To Rule Them All. Having a formal proof of impossibility is nice.)

***

I still haven’t explained why machine learning research can take over your life.

Well, I suppose I have, in a roundabout way. Machine learning experiments can be very arbitrary. Not even the legends in the field can get away with avoiding hyperparameter tuning. It’s a necessary evil.

It makes the field feel like one huge casino. You pull the lever of the slot machine, and hope it works. Sometimes, it does. Or it doesn’t, at which point somebody walks up to tell you that slot machine hasn’t worked in 10 years and you should try the new slot machine everyone’s excited about. Machine learning is very much like folklore, with tips and tricks passed down over the generations.

We understand many things, but the slot machine’s still a slot machine. There’s unavoidable randomness that will ruin your day. And worse, it’s a slot machine where your job or funding or graduation is on the line.

In the game of machine learning, you get lucky, or try so many times you have to get lucky. The only way to guarantee success is to do the latter.

That means experiments. Tons and tons of experiments. It doesn’t help that the best time to run experiments is when you’re about to take a break. Going out for lunch? Start an experiment, see how it’s doing when you get back. Heading out for the day? Run an experiment overnight, check the results tomorrow morning. Don’t want to work over the weekend? Well, your computer won’t mind. We’re in a nice regime where we can run experiments unattended, which is great, as long as your code works. If your code breaks, good luck fixing it. Every day you can’t run experiments is one fewer night of computation time.

It’s the kind of pressure which pulls in workaholic mindsets. You don’t have to fix your code tonight, just like you don’t have to maximize the number of level pulls on the slot machine. I’m sure you’ll get lucky, even if you miss a day or two. It will be fine.

If there was a way to make machine algorithms Just Work by, I don’t know, sacrificing a goat under the light of the full moon, I’d do it in a heartbeat. Because if machine learning algorithms Just Worked, there are plenty of ways I can make up for killing an innocent goat.

Good thing goat sacrifices don’t do that, because I really don’t want to add that to my list of “things that work for unsatisfying reasons”. That list is plenty full.

***

At this point, you might be wondering why I even bother working in machine learning.

Truth is, all the bullshit is worth it. There are so many exciting things happening, and by this point my tolerance for these issues has grown by enough that I’m okay with it. Compared to theory, running experiments is garbage, but it’s exciting garbage.

The theoretical computer science friends I know probably think I’m insane for putting up with these conditions. I’m insane! Oh well. What else is new.

Here’s us, on the raggedy edge. If that’s the price to pay, I’ll pay it.

The javelin is far ahead of her and moving far faster. The colonists will have plenty of time to get comfortable. There will be something at Sirius by the time she gets there. Maybe. It’ll be friendly, maybe. And if not, she can keep improvising.

(Ra)

-

I Got Fruit Opinions

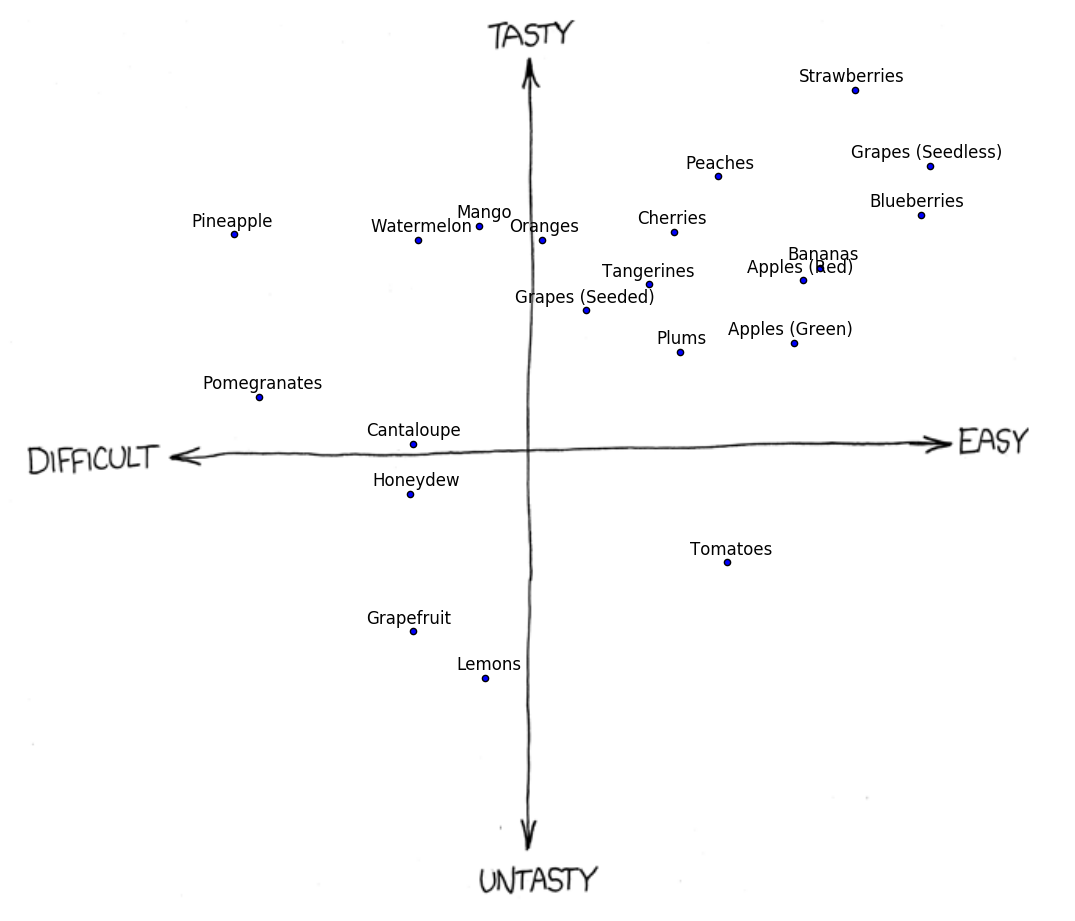

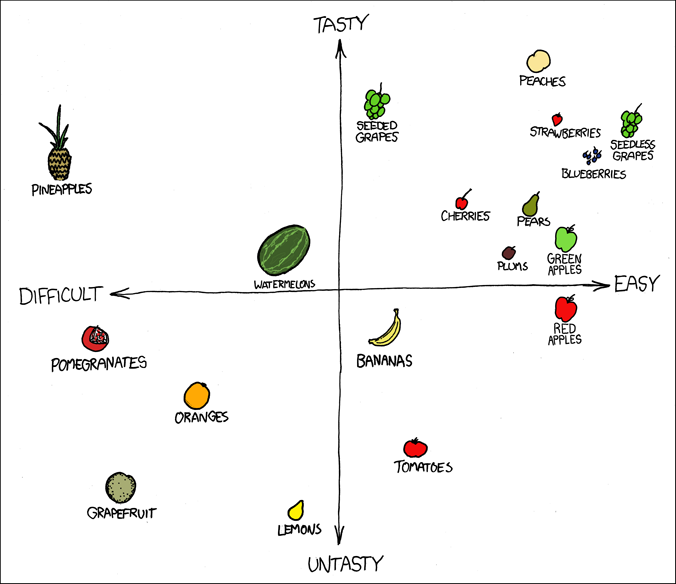

CommentsBack in 2008, Randall Munroe, creator of xkcd, put up this comic.

In a perfect storm of bikeshedding, this comic was by far his most controversial ever. He got more email from this than his endorsement of Obama. It seemed that everyone had a different opinion about fruit, and wanted to tell Randall exactly how wrong he was.

For a while, I’ve wanted to know what the average fruit opinion is. One day, I decided to stop being lazy and make a survey for this.

Survey Design

Participants rated each fruit’s difficulty and tastiness on a scale from 1 to 10. I shared the survey among my Facebook friends, the xkcd subreddit, and the SampleSize subreddit. One of my friends reshared the survey to the UC Berkeley Computer Science group.

Along the way, I got some comments about the survey’s design. My surveyed population is biased towards people who frequent those subreddits, and placing the xkcd comic at the start of the survey biases participants. It’s true, but in my defense, I wanted to give context for why I was conducting this survey, and the survey is about fruit. Literally fruit. It wasn’t supposed to be a big deal.

Analysis

In total, I got over 1300 responses. Before going into results, fun fact: everyone’s fruit opinion is indeed unique. No two responses had the exact same fruit rating. To be fair, it would be more surprising if this weren’t true, since I asked for ratings on over 20 different fruits. In fact, it would have been incredibly strange if I did find two people with the exact same rating.

Results

The five most difficult fruits are

- Pineapple

- Pomegranate

- Honeydew

- Grapefruit

- Cantaloupe

Pineapple and pomegranate are the clear losers here. Honeydew, grapefruit, and cantaloupe are all roughly tied in difficulty.

The five easiest fruits are

- Seedless Grapes

- Blueberries

- Strawberries

- Bananas

- Red Apples

No surprises here.

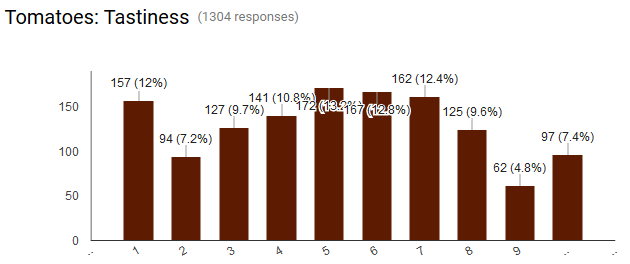

Now, onto taste. The five worst tasting fruits are

- Lemons

- Grapefruit

- Tomatoes

- Honeydew

- Cantaloupe

As a fellow grapefruit hater, I approve. As a fan of cantaloupe, I question people’s judgment.

The five best tasting fruits are

- Strawberries

- Seedless Grapes

- Peaches

- Blueberries

- Mango

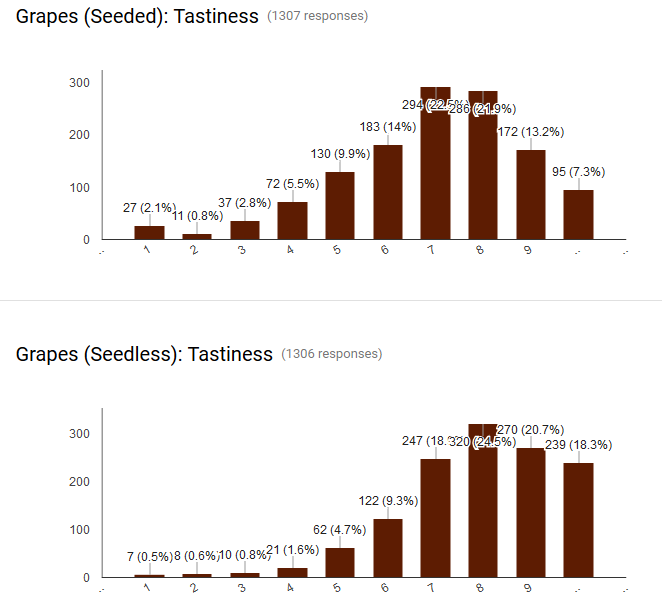

Personally, I’m surprised seedless grapes was 2nd, while seeded grapes was 13th. It’s not a small difference either - here are the two histograms.

Seems like it was hard to disentangle the taste of the fruit from its difficulty.

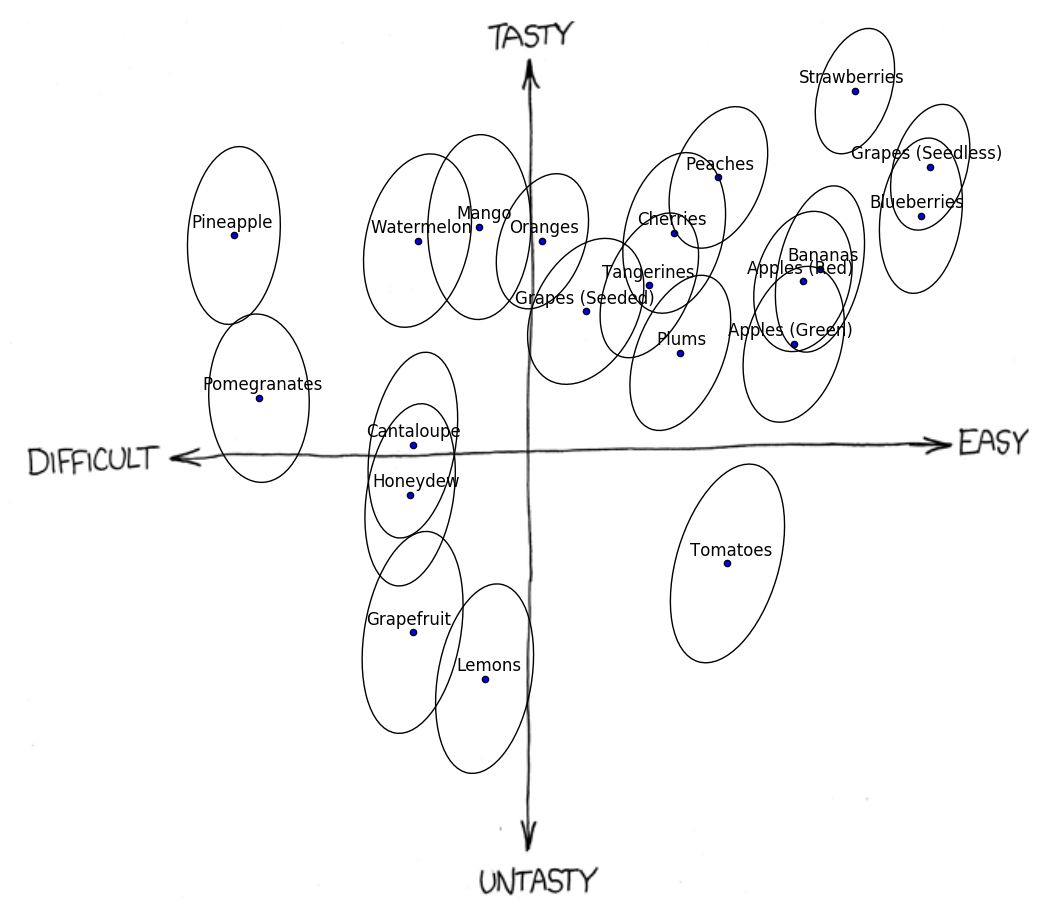

Finally, controversial fruits. I measured this by fitting a normal distribution to the cloud of replies for each fruit. The distribution is fitted to difficulty and tastiness simultaneously. A fruit is controversial if its normal distribution has large variance.

The five least controversial fruits are

- Strawberries

- Seedless Grapes

- Oranges

- Blueberries

- Tangerines

By definition, this shouldn’t be surprising.

The five most controversial fruits are

- Tomatoes

- Grapefruit

- Mango

- Watermelon

- Lemons

Yep, the tastiness of tomatoes was definitely controversial - this is almost like a uniform distribution, compared to the histograms for grapes. Also, congratulations to mango, for being both controversial and in the top five tastiest fruits.

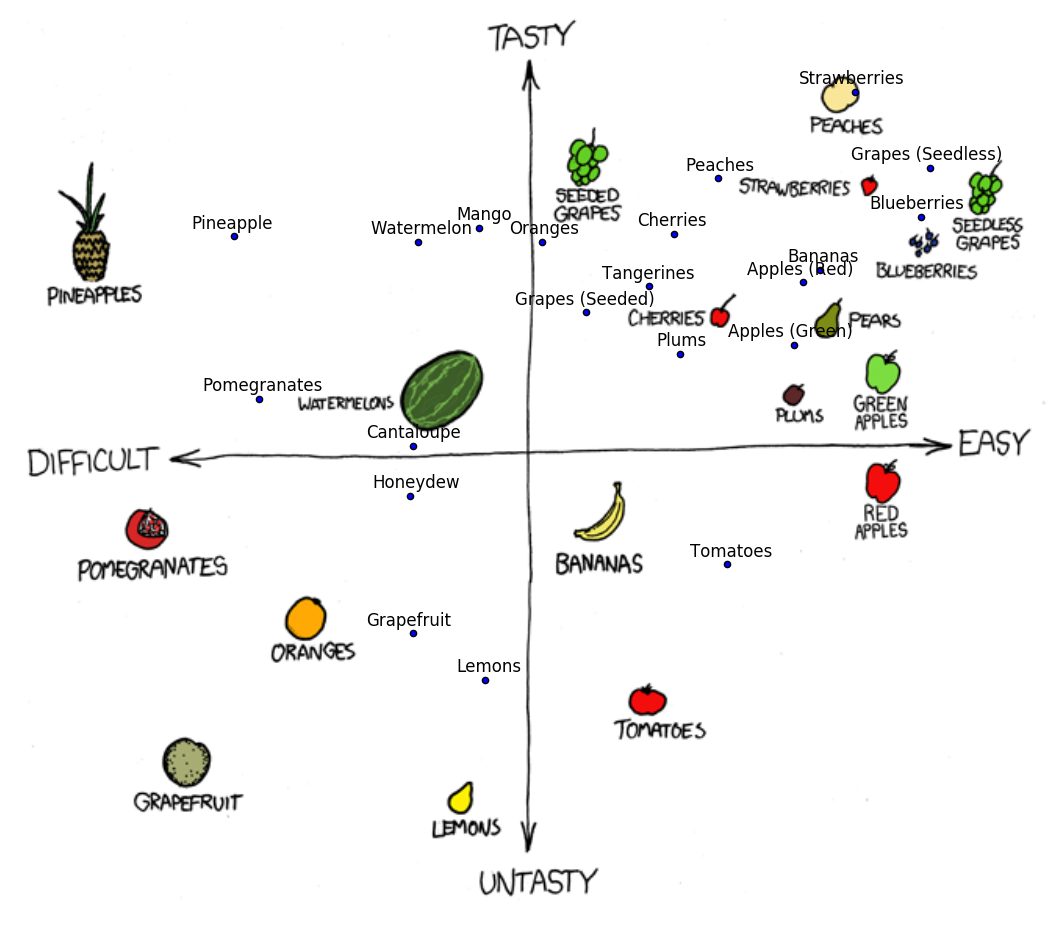

Graphs

I had to bend the numbers a little bit here. It turns out the average tastes for each fruit are a lot closer than their average difficulty. Stretching the taste-axis exaggerates the relative difference between fruits without changing their ranking.

Here’s the same plot overlaid onto the original comic, if you want to compare and contrast.

Finally, here’s the plot with confidence ellipses from the fitted normal distributions, to visualize controversy. Don’t read too much into the absolute size of each ellipse. Only a small fraction of responses actually lie within each ellipse, but drawing a 90% confidence ellipse would have made the ellipses overlap more than they already do.

For the technically inclined, a CSV of responses can be downloaded here, and the code used to create these graphs can be seen here (requires NumPy and Matplotlib).