Authentic Imperfection

Auto-Tune is great.

I used to be ambivalent on this, but got radicalized by a video from Sideways. I will give the quick version.

Auto-Tune is one of many pitch correction tools that can be used to tighten up slightly off-key vocals. Its intended use was to reduce time spent getting the perfect take, by doing light adjustments to an existing performance.

Although intended as a background tool, it entered public consicousness when artists like Cher and T-Pain deliberately used it to an extreme degree because they liked the audio effect. This was special at the time, but ever since, they have been accused of not being real singers. T-Pain especially, even when there are many recordings of T-Pain singing live.

A ton of music artists use Auto-Tune, because audience expectations around music production have escalated rapidly, causing the baseline of “good singer” to rise. From just a musical standpoint, we get better music - cool! From an overall standpoint, it’s more mixed.

These tools have advanced to the point where pitch correction can be done live in real-time, and once again, most people can’t tell it’s happening. Concerts sound better, but no one will ever acknowledge this, thanks to the public stigma around Auto-Tune, and the assumption that if you use it, you don’t have talent.

This has led to an interesting place. Either your music performance needs to be perfectly pitch corrected, or it needs to be slightly off from perfect. The latter is implicitly considered a sign of authenticity: no one would tune themselves to sound wrong.

Sideways’ channel is specifically about movie musicals, so the video segues into how the music from the Les Miserables movie is really bad, but there’s something novel here. We want pure music, but only some kinds of music production count as pure.

This video is from 2020. Within three years, ChatGPT and DALL-E came out, and we speedran this discussion all over again.

* * *

I’ve been thinking about the anger surrounding generative AI. There are common themes. It uses too much energy, it violates too many copyrights, the content isn’t even good.

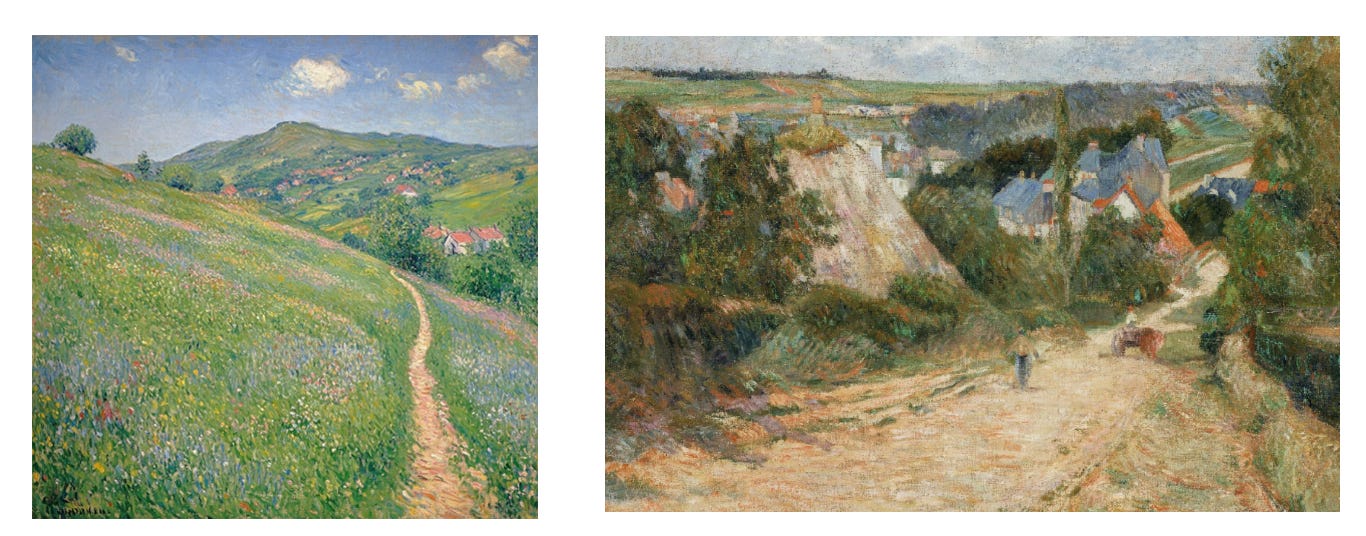

I think the last point was easier to argue in the past and has gotten harder over time. What does it even mean for content to be good? It’s a very fuzzy, subjective thing, and there are recent surveys suggesting even the AI haters can’t tell all the time. Last year, Scott Alexander of Astral Codex Ten ran an AI art Turing test. To keep things fair, he took the best human images and best AI images, meaning human art from famous artists, and AI art from prompters skilled at removing obvious tells of image generation.

The median responder only identified 60% of images correctly, not much above chance. And, interestingly, when asked which picture was their favorite, the top two pictures were AI generated, even among people who said they hated AI art.

So what’s going on here?

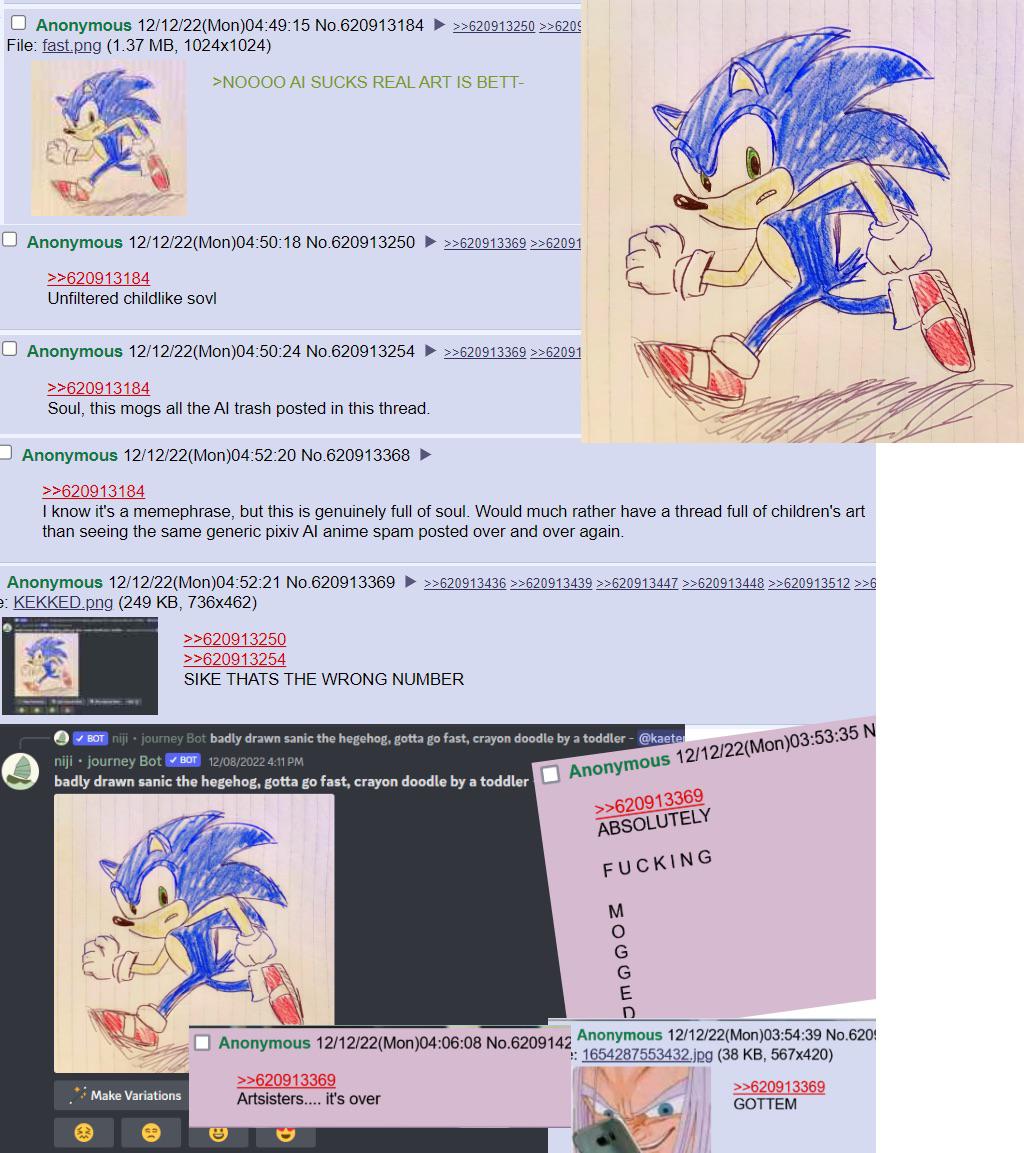

When people complain about AI slop, I see it as a complaint against the deluge of default style AI images. First, it was hands with the wrong number of fingers. Then it was the overproduced lighting common to DALL-E and Midjourney outputs. Then it was the Studio Ghibli style and vaguely yellow filter common to ChatGPT generations. But these aren’t the only things image models can do. They’re just the quickest, trendiest thing. The things that become trendy are the things which become obviously artificial by sheer volume.

I’ve spent a very large amount of time overall with Nano Banana and although it has a lot of promise, some may ask why I am writing about how to use it to create highly-specific high-quality images during a time where generative AI has threatened creative jobs. The reason is that information asymmetry between what generative image AI can and can’t do has only grown in recent months: many still think that ChatGPT is the only way to generate images and that all AI-generated images are wavy AI slop with a piss yellow filter. The only way to counter this perception is though evidence and reproducibility.

Like Auto-Tune, there was originally a novel effect to the artificiality, and now it’s just wrong. It’s annoying when Claude Code says “you’re absolutely right!”. It’s weird when LLMs use em dashes, to the consternation of writers who wish they could use them without getting accussed of AI.

There are two reasons why this [em dash] discourse must be stopped: The first has to do with the way generative AI works; the second has to do with the fate of the human soul.

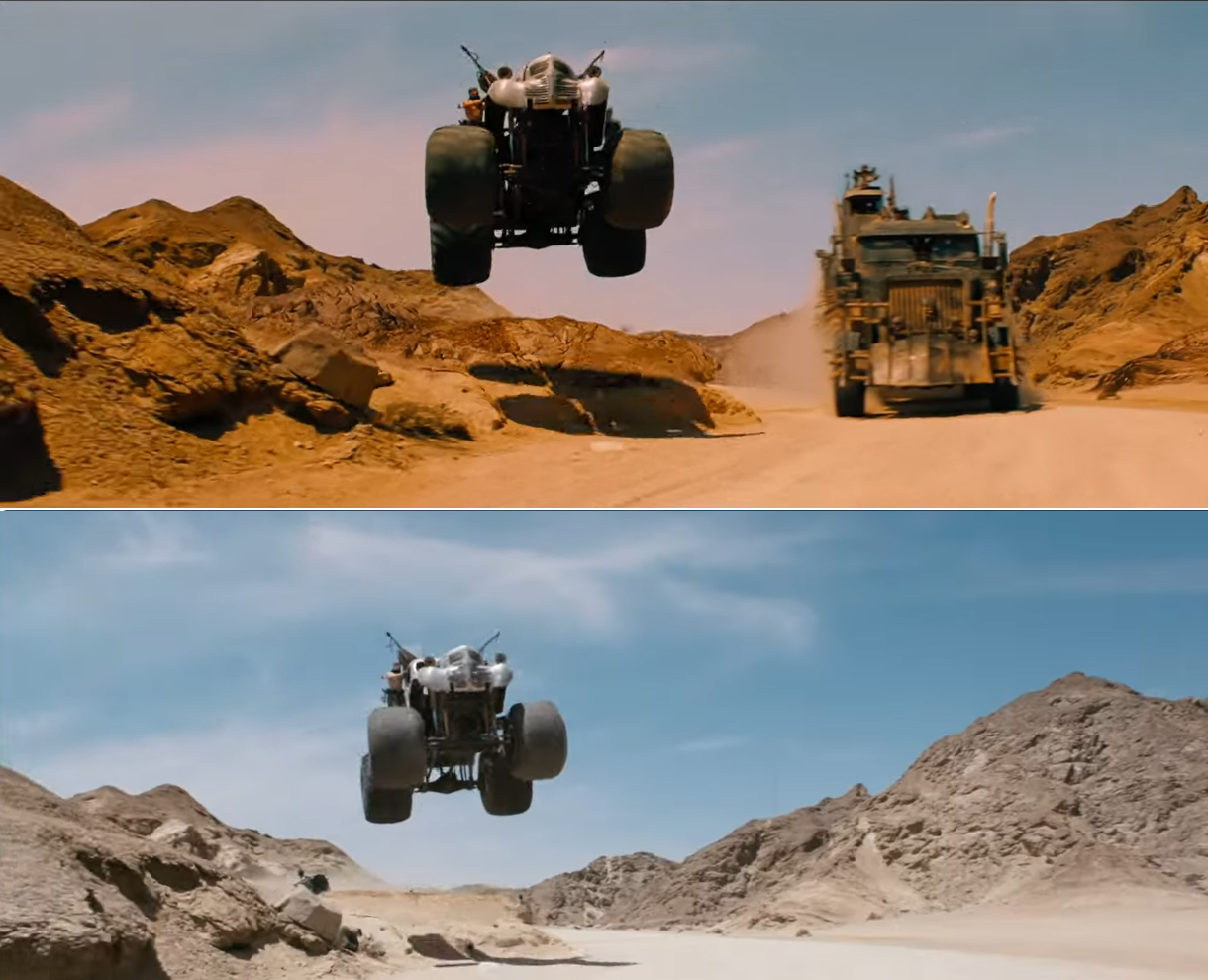

But, importantly, you can make people forgive the artificiality if you try. We’ve seen this happen in all forms: AI text, AI music, older forms of computer generated content like CGI. Mad Max: Fury Road is one of my favorite movies, and one narrative about the movie was its heavy use of practical effects. This was said with the air of “practical is better”, even when Fury Road used digital VFX in nearly every shot. But if you call it digital VFX instead of CGI, no one cares! One is the boring phrase and one is the bad phrase. CGI implies less work than raw human effort, even when the digital VFX industry is notorious for its long hours, poor pay, and unreasonable deadlines.

Comparison by Matt Brown from Toronto International Film Festival

In the comparison above (movie top, original shot below), obviously the main difference is the addition of the truck and the color correction. But did you notice the rock added to disguise the ramp the car jumped off of? (Look under the tires if you didn’t.) I know this is table stakes, everyone does it, but these adjustments are all over the movie, and it’s the kind of attention to detail that means something to me. Intent of that form can shine even when mediated by computers.

I don’t think people really care about AI or not. It’s more of a proxy complaint for whether they can see vision or taste. Or maybe people are shortcutting AI usage as a sign the user doesn’t have vision or taste, out of an assumption that someone with vision would do the work on their own.

We want to see the people behind the curtain. We care what they are trying to say. We interpret idiosyncracies and failings as style. When you learn something was generated artificially, this implicit contract breaks. The idiosyncracies of AI are too correlated to be charming.

I’ve seen a lot AI due to being a highly online person who works in AI, and don’t like most of it, but I had a lot of fun with the AI Presidents discuss their top 5 anime video that metastasized into a trend of AI Presidents discussing nerd culture. There was something honest in its absurdity, where the AI layer was generating the voices, the taste layer was deciding which president would take which role, and it comes together beautifully. Yet I’d admit that if I learned the script was written by an LLM, it would lose some of its magic.

As much as we celebrate imperfection, digital imperfection is a step too far. We see AI in the lens of automation, where failure cannot stand. People don’t want tools that give them more ways to fail, they want agents that make failure impossible. We don’t have them yet and would find ways to complain about them even if we did. Until then, in the uncanny valley of competence, at least the flawed can be kings.