The 5 Year Update on Skipping Grad School (and Whether I'd Recommend It)

In 2015, I was in my last year of undergrad and had a lot of angst about whether I should apply to PhD programs. I ended up not applying, writing a 6000 word blog post explaining why. The short version is: lots of imposter syndrome, disillusionment about whether I could handle the marathon of research, wavering faith in doing research at all, and an eventual decision that if I wasn’t sure about research, I couldn’t turn down the money and steady work I could get from industry.

That post wasn’t really meant to be educational. It was more an expression of the feelings I had, written for myself rather than anyone else. But it resonated with a few people, and I’m happy it did.

After that, I interviewed around, got an AI residency offer from Google Research, and did that for a year. I then stayed there full-time and now work on the Robotics team. I primarily work on applying imitation learning and reinforcement learning to robot manipulation problems.

I don’t have regrets about deciding to skip a PhD. Given what I knew about myself at the time, it was the right choice. But it’s been 5 years since then, and 5-6 years is about the length of a computer science PhD. There’s a nice parallel there, so I figured I’d write an update on how things have gone. In particular, I wanted to take a step back and evaluate how my life’s differed by starting in industry instead of a PhD program.

Disclaimers

- This is based on what I believe grad school is like, but my model could be incorrect.

- This is specific to machine learning PhDs. ML is in a very unique position that doesn’t generalize to other fields. Extrapolate with caution.

- I was pretty lucky to get an industry lab research offer. 2015-2016 was a crazy year for deep learning. AlphaGo had just won against Lee Sedol, OpenAI was founded, and companies were going crazy on hiring. Google had never done an AI residency before, so they didn’t fully know how it would go and it was less competitive to get in. Things would be different if I had taken a generic SWE job offer instead.

- Working on this post has taught me that everyone’s academic and industry lab experience is wildly different. Like, completely contradictory along every axis. My experience won’t be typical because no one’s experience is typical. The space of outcomes is too big. Even if your outcome doesn’t line up with mine, I hope this post conveys the possibilities.

- Conveying the possibilities made this post long. Sorry. I tried to make it shorter and I failed.

Research Confidence

One reason I didn’t apply to PhD programs was that I wasn’t sure I was in the same weight class of research ability as my peers. My undergrad research was never good enough to publish. Meetings felt like I was desperately trying not to drown in new topics. It was all a bit much. When I talked to friends in my year, they reassured me and said I’d do well in grad school. I disagreed.

In hindsight…I’m not sure if they were right, but they weren’t wrong. I’m more calibrated on my abilities now and think I definitely could have kept up, albeit not superstar tier.

I think the reason I underestimated my ability is that getting through the first few walls is the hardest. It’s surprising how much easier research got with experience. It’s still hard, but I have a better handle on how projects organize themselves and how to follow them through. (As well as how they can fall apart, which is an unfortunate lesson that everyone learns eventually.)

When I imagine the world where I did a PhD instead, I don’t think my research self-confidence would be that different. It was at a near bottom in undergrad, and regardless of where I went, it would have improved. I was getting better, I just didn’t realize it yet.

Research Interest

I discovered over the past 5 years that I love being a spectator of research, but the burden of being a continual producer of new research is just too great for me.

This is a quote from the Ph.D. Grind, and 2015-me agreed with this as-is. Learning about new research is awesome, in the same way that taking classes is awesome. Paper authors and teachers think carefully about how to deliver knowledge as quickly and clearly as possible to your brain. If the paper’s confusing, or they taught the course poorly, they’ve failed.

Reality is unfortunately not set up this way, and since research is about understanding reality, it’s much more time consuming and draining to learn something new. In exchange, the insights can be much more satisfying.

I would now amend the quote above to:

The burden of being a continual producer of new research is too great without careful management.

I got much better at work-life balance once I left university. This is definitely at the cost of my productivity. I got more done in school, but it wasn’t sustainable for my mental health. There’s a sweet spot where I feel I can do research without burning out, and in that sweet spot research is great. In short, I could be doing more, and I choose not to because I have other priorities and life is more fun that way.

It’s intertwined with the Research Confidence section, but another reason I was disinterested in research was that failing to make progress in undergrad made me very pessimistic I would do anything meaningful in research.

When I don’t do research for a while, I miss the feeling that I’m in touch with the cutting-edge and playing a hand in shaping the future.

[…]

When I do research for longer, I realize how much of a novice I am and how unlikely it is any of my contributions will be important.

I’ve since been part of some noteworthy papers like QT-Opt and GraspGAN, and that’s helped me believe in myself. When I got my first email asking for help reproducing a paper, I was pretty excited. They wouldn’t be asking unless they were paying attention! Seeing concrete threads of influence between my work and changes in the research landscape makes it easier to keep going.

I’m guessing my interest is higher than it would have been if I went to grad school. The papers I was on that made big splashes were from large projects with 10+ authors. Those don’t tend to come out of academic ML labs. In a PhD setting, I likely would have worked on more papers that each had a smaller impact, and although that might add up to a large total impact, it would have been less fulfilling because I wouldn’t notice it as easily.

Research Reputation

By reputation, I mean: how often are you asked to peer review for a conference or journal? Are you asked to be an area chair? If you went to give a talk somewhere, how much of the interest would be driven by your name, rather than the subject of your talk? People usually call this “status”. I’m using reputation because it’s alliterative.

I find it all kinda grimey to think about, but it does matter, especially for research. Reputation matters because it’s the way you stay employed. If you want to keep doing research, you need to both be good at research, and be known as someone who’s good at research. Right now, the demand for ML / AI talent is still way bigger than the supply of PhDs, so companies will take anyone they think can do the work. This won’t last forever, and credentials are the first filter that’ll appear when it stops. Ask people in electrical engineering. I’ve heard EE companies used to hire straight out of undergrad, and now it’s hard to get anywhere without at least a master’s.

Machine learning might also be in a bubble. I’m not going to claim anything about whether that’s true, but if it is, then the climate could change very quickly. Therefore, I’m reluctant to rely too much on the past when planning my future. To quote John Langford at the Real World Reinforcement Learning workshop, “if there is one piece of machine learning which is going to crash, it’s going to be reinforcement learning”. Unfortunate for me, given what problems I find interesting!

There’s two kinds of research reputation: endorsement, and influence through publications. Endorsements are easier to get. You can give a good talk, make an impression on someone when you mingle at a conference, or contribute useful ideas during a research brainstorm within your lab. But these endorsements aren’t permanent. It’s tied to the people you work with and the institution you work at. People change jobs, fortunes turn, and if everyone who knows you leaves, then you’re left with nothing. Word of mouth has a short reach.

Endorsements can be very useful, if you have them from the right people. If a professor is willing to vouch for you, that means a lot, because they’ve seen many prospective students, are calibrated on what a good researcher looks like, and it’s common knowledge that they’re calibrated. That means they can make pretty strong cases in your favor if they think you deserve them. It’s why letters of recommendation are important for PhD applications. A recommendation from a senior industry researcher can be good for similar reasons.

Outside of these cases, most recommendations mean very little. Being known as “the person who knows X” is nice, but this alone is not enough, because lots of people “know a guy”. The recommendation only means something if the person hiring you knows how calibrated the recommender is, and only a small number of people have seen enough researchers to be calibrated. For a PhD program, a letter from a software internship saying you’re the best intern they’ve ever had means little. A letter from a professor that says “they’re a genius” can be enough by itself. It was for John Nash.

If you’re confident you want to keep doing research for the rest of your life, you need concrete, visible proof of your skills. For research, that means publishing. Using h-index as a filter isn’t perfect, and everyone knows it isn’t perfect, but it’s used all the time anyways. Getting a higher h-index requires publishing, and getting a PhD is a surefire way to force you to publish. Your papers may not be the best, but they’ll be out there, and once the papers are out there, no one can take them away from you.

When I got the AI residency offer, I treated it as a 1 year trial run of whether I wanted to keep doing research. After that year, I decided that yeah, research was cool, and I liked Google, so I went for a riskier plan: get enough publications out of my industry research to create a PhD-equivalent body of work. If I got there, no one would care I didn’t formally have a PhD. This wouldn’t qualify me for any faculty positions, but I was okay with that.

That plan hasn’t gone perfectly. I’ve been on some papers, but not that many. I’ve reviewed for conferences, but I get the feeling that the ML reviewer pool is so starved that organizers are continually scrambling for any reviewer they can get, so it doesn’t mean much. Working on big projects is good for driving the field, but the papers that come out of them are often treated as “the Apple paper” or “the Uber paper”, rather than “the paper by X & Y”.

However, I have written for this blog more seriously, and somehow my blog is now the biggest reputation boost I have. It’s not the same as a paper, but it’s another way for me to put out work that demonstrates how I think through research problems. My post about deep RL is still my most viewed post, and I’d like to think it helps get my foot in the door. In the end, what matters is influence on the research community, and well-cited publications aren’t the only way to achieve that.

If I had done a PhD, my reputation would probably have been equal. I would have written for this blog either way, and evidently it’s the main reason people know who I am. My takeaway is that more people should start blogs! I don’t know why they don’t. Maybe they’re too busy writing papers or something 😛. Joke’s on them, I get to use emojis and they don’t.

Research Ability

I realize I just spent a section saying people should publish, but a PhD isn’t about getting a lot of publications. It’s about learning how to form and attack a long term research thesis, with publications as a natural byproduct. To borrow fighting game advice, practice isn’t about winning, it’s about learning something, and that will make you win more in the long run.

This counterfactual is the hardest for me to judge, because advising in industry vs academia is so different.

A good advisor will help you figure out what problem you should try tackling next, explain why that decision makes sense, and repeat this process until you can do it yourself. This is what people mean when they say you’ll develop research taste. If a professor doesn’t do this, then they aren’t a good advisor, and professors want to be good advisors. It’s how they get their reputation.

No one is required to give you this mentorship in an industry lab. The more top-down the lab, the truer this is. Industry labs tend to organize themselves around a grand vision, like “we can build a quantum computer”, or “all AI needs is good scaling”, and although these are very broad theses, more of the research direction is already sketched out by the team leads. That leaves less research direction for you to figure out.

So, you might not have a mentor in industry, but in a PhD program, it’s possible your advisor doesn’t mentor you either! Based on talking to research scientists at Brain, a surprising number have said their professors were too busy to help them much, compared to their labmates. And if you’re stuck figuring out research with your labmates, then your labmates in an industry lab will include people who’ve already navigated a PhD. Fewer people are obligated to give you mentorship, but more people could give you mentorship.

If you figure out whether your boss / advisor will be good before signing anything, that solves everything, but doing so is easier said than done. Everyone I know who’s left Google did so because they didn’t get along with their manager, and to me it feels like a cosmic roll of the dice whether that happens or not. Getting a good professor is a similar roll with higher stakes. A PhD advisor has more power over your life than a manager does.

I think the grad student \(\rightarrow\) advisor relationship can be felt out more if you make good use of visit days, and talk to current PhD students to get their take on how things are going. So the stakes are higher, but you have slightly better odds. (You might be able to get the same level of access for industry if you’re good at pestering recruiters.)

I got lucky and had mentors in industry who encouraged me to consider where the field was going. I think on expectation, if I was in a PhD program, my research ability would be similar, but there would be high variance on how it could’ve played out.

Money and Freedom

Money isn’t my first priority, but I’m not going to ignore it.

If you only care about the money, doing an ML PhD just doesn’t make sense. Unless you discover something revolutionary that starts a bidding war, 5-6 years of ML engineer / data scientist salary + compounding returns from investing in index funds will get you more than most post-PhD jobs.

You don’t do a PhD for the money, but money tends to correlate with freedom, which is one reason people do a PhD. On that front, friends in academia have told me very different stories. Some told me they felt they could do anything, while others told me about labmates who had to teach courses they didn’t want to teach, or do research separate from their thesis to pay the bills.

The common thread in those stories was that PhD students should get as much unconditional funding as possible. Students in good situations had NSF fellowships and enough unconditional grant money from their advisor to do whatever they wanted. Students in bad situations had more of their funding come from grants with narrow proposals, requiring them to do work that matched the proposal rather than the research they were most interested in. Good advisors try to shield their grad students from these situations, but not all professors get unconditional grants.

In contrast, ML industry labs have one source of funding (the company), and it’ll pay enough that you won’t need to think about side hustles. You will probably have fewer responsibilities outside of research, but you won’t have radical freedom. I remember a dinner at NeurIPS, where a professor said that sometimes the best thing for a grad student is to have them go read textbooks for 9 months to learn all the math foundation they need for their research interests. This is an example of something you can do in academia that you can’t really do in industry.

It’s also possible that your company will lay-off your research lab without much recourse. To give recent examples, in 2014 Microsoft closed their entire Silicon Valley research lab. In 2020, UberAI downsized and Alphabet shut down Loon.

The freedom in an industry lab isn’t obviously worse than a PhD. A person with stable funding in an industry lab likely has more research freedom and time than a PhD student with unstable funding. On average though, I’d say that PhD programs have the edge.

Research Direction

I started undergrad planning to double major in math and CS, and like theoretical CS in general. If I had gone to a PhD program, there’s a real chance I would have ended up in learning theory instead of robot learning.

Many industry labs have good theory people, but on average an industry lab will be more experimental. The argument is, industry labs have access to bigger computing clusters, therefore it’s more scientifically interesting if industry labs work on projects that exploit the comparative advantage of more compute, because this produces research of a different flavor. (I would link a post that argues this with examples, but it was hosted on Google+.)

I find this argument reasonable, but it puts pressure on theoretical work. Why should the industry lab pay you for this work, when you aren’t using any of industry’s resources and could do identical work in academia? All you need is your brain.

From what I’ve seen, theory work from industry labs is usually a hybrid of new theory, along with experiments showing that it works. Otherwise, pure theory work is rare, unless there is a high certainty path between that theory and something revenue generating. In those scenarios, it’s important for the company to hire theory people to stay on the cutting edge.

Speaking more generally, the subfield you pick affects the number of job openings you’ll find in industry. If you can’t be happy unless you’re in a niche subfield that industry doesn’t value yet, academia might be your only option.

Personally, my research interests aren’t perfectly aligned with my day-to-day work, but it’s aligned enough that I’m willing to bend in favor of the trade-offs it comes with. The good part of robot learning is that getting things to work in the real world makes you directly hit hard, interesting problems that have to be solved for ML research to be useful. The bad part is that you have to deal with the real world.

I’d probably have done more theory if I had gone to a PhD program, but it’s hard to say whether that would have continued long-term, or if it would be a summer fling before going back to more practical work. Most likely, I’d be working on the same problems I am now, with a different perspective on how to attack them.

Day-to-Day Work

When I talk to people considering skipping a PhD, a common worry they have is that if they join an industry research lab, they’ll be expected to do more software engineering work and less research.

The first piece of advice I’d give is that even if you get a PhD, you’ll probably do grunt SWE work. Research tools will always feel deficient, because your research will uncover new problems, and it’s unlikely the perfect tool exists for a problem no one but you has seen before. These tools will therefore almost always have sharp edges that cut you a few times. Doing a PhD will not save you - you will be debugging garbage your entire life.

(from xkcd)

The second piece of advice is that I think getting boxed into non-research work is a real, valid concern. Unfortunately, every industry lab is different, so I can’t recommend much besides asking friends who work in those labs, if you know any. In my experience, if you like a project, you won’t mind the grunt work as much, so I’d optimize for that first.

Coming in through the AI residency program meant I did research from day 1, and by the end of that year I had convinced enough people to get research roles in future projects. However, I’ve also done a lot of SWE work for that research, because those projects often used large distributed systems that were tricky to understand, build, and debug. I think my day-to-day work would’ve been similar in academia, I’d just be debugging different sorts of distributed systems. Such is the fate of using deep learning.

Non-Research Skills Learned

There are many skills outside of direct research that will help you with your research.

For example, software engineering. Industry will teach you how to write better code. If you don’t do code reviews or write unit tests, your code isn’t getting checked into the repository. Even if no one teaches you good code habits, you’re embedded in a company with non-researcher SWEs and will naturally acquire good habits through osmosis.

Better coding will make you a better researcher. Most PhD programs don’t teach software engineering or best practices. I understand why, you’re supposed to learn it in undergrad, but…okay, I’m going to rant for a bit. Pardon the side track.

Research code is, as a rule, not very good. I used to think this was fine and even desirable. I no longer think this is true.

There is this longstanding idea that research code is bad because researchers don’t know if their ideas will work. If the idea doesn’t work out, then time spent cleaning up the implementation is wasted, compared to spending time on new ideas. I 100% agree with this. All the very good researchers I know try lots of ideas. (Pure volume isn’t enough, they try their ideas with purpose, but they try a lot of ideas with purpose.)

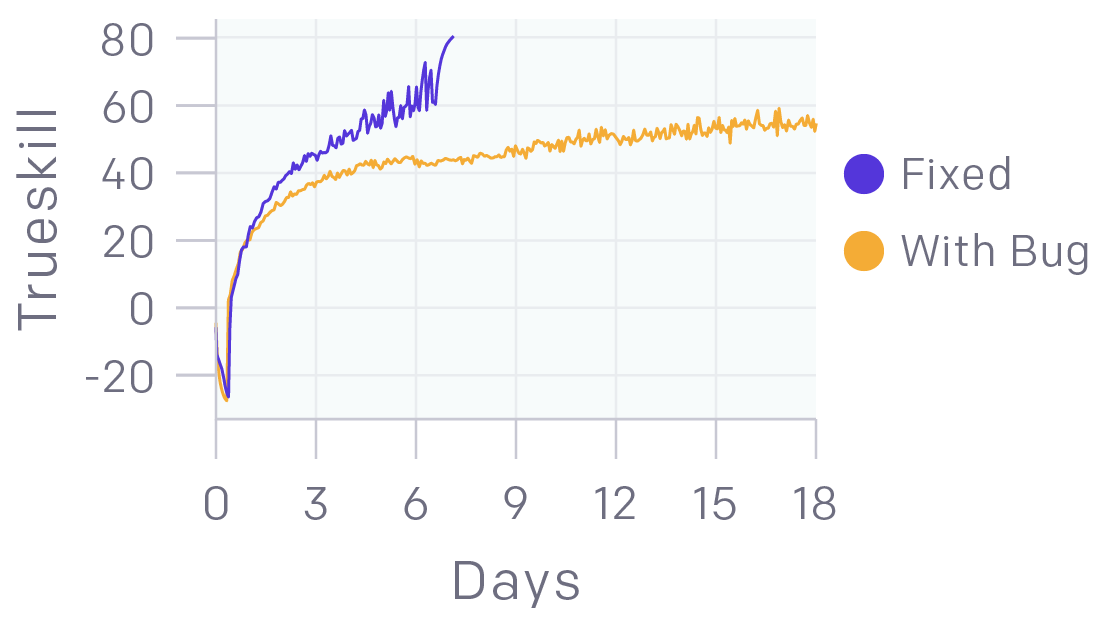

My issue is that people take this too far. Look, writing beautiful code takes time. Writing legible code does not. Real variable names and useful comments reduce the complexity of the mental model of your code, which makes it easier to catch bugs. This is especially important in machine learning, since bugs don’t surface as compiler errors, they surface as mysterious 20% drops in performance in a pipeline that mostly works.

(Learning curve of OpenAI Five, before and after fixing a bug where the agent was heavily penalized for reaching level 25. Learns anyways because machine learning finds a way.)

Since performance drops could come from bugs, or bad data, or a bad model, you want to make sure bugs are easy to quickly prove or disprove, since they can be fixed the fastest. Doing some code cleanup will save time in the long run, even if you’re the only one who looks at your research code. Your collaborators will thank you. This is especially true if your “collaborator” is future-you trying to run an experiment for a reviewer rebuttal 2 months after you’ve thought about any of the relevant code.

Now, do you need to go full code review to write good code? No, I don’t think so. Another set of eyes helps, but PhD students have good technical skills and are perfectly capable of reviewing their own code. Just, actually do it. Please.

(end rant)

A PhD program may not teach you coding, but on the flip side, an industry job likely won’t let you teach a course. You may have some chances depending on the company, but you’ll have many more chances in academia. Teaching will also make you a better researcher, because it forces you to clarify ideas until newcomers can understand them, which is the exact skill you need when writing papers. Not to mention it can be rewarding by itself.

A PhD program will also provide more mentorship opportunities. In academia, the totem pole is professor > postdoc > grad student > undergrad or master’s students. Going to a PhD program means you aren’t on the bottom anymore, and you’ll get to mentor undergrads that want to try research. Whereas in industry, if you join out of undergrad, you’re entering at the bottom of the totem pole and will have fewer mentoring opportunities until interns come, which is a seasonal thing. Mentoring helps because it exposes you to a wider variety of thinking, and sometimes solving a research problem just requires the right perspective.

Personally, I believe in all of coding, teaching, and mentorship, but right now I do more coding + teaching, where teaching is defined broadly enough to cover writing blog posts and presenting in reading groups. In a PhD program, it’d likely be weighted towards teaching + mentorship instead, where teaching means TAing a class. I did like my SWE internships in undergrad though, so I could see myself getting into coding and becoming a SWE proselytizer in a PhD program. Who knows?

Social Life

I’m more of an introvert, and didn’t talk to a lot of people growing up. I’m not depressed or unhappy by any means. Through practice, I’ve developed a long, winding maze of entertainment and side projects that keep me busy if I don’t have the energy to catch up with friends. The problem is that the maze is too effective, sometimes it takes a long time to get out, and when I do I usually wish I had exited the maze sooner and socialized more.

Undergrad life shook that maze in a way that working life hasn’t. When everyone lives near campus, everyone goes to campus whenever an event’s happening, and you can serendipitously run into friends in the street, it’s just a lot easier to meet people and hang out.

Those things happen in industry too (there’s a reason water cooler chat is a thing), it just doesn’t happen to the same degree. The demographics are also different. I find it harder to relate when people talk about their kids, or buying a new house.

If you go into industry, you’ll mostly see people on your team. If you go to grad school, you’ll take fewer classes and mostly be spending time in your lab. In both cases you get fewer chances to meet new people than undergrad. I suspect the largest factor for social life is location, rather than industry vs grad school, so it’s hard to say how this would go.

So, Should You Do a PhD?

| Section | Verdict |

|---|---|

| Research Confidence | About equal |

| Research Interest | Higher from industry |

| Research Reputation | About equal |

| Research Ability | About equal, but high variance |

| Money | Much better |

| Freedom | Slightly worse (compared to top CS program) |

| Research Direction | Slightly misaligned, but not by much |

| Day-to-day work | Similar |

| Non-research skills | Less mentoring, more coding |

| Social Life | Very dependent on location, hard to say |

After totalling this up, I’d say I came out ahead by skipping a PhD. I don’t have any plans to go back to academia. I still can’t say I’ll never go back, but right now I feel I can achieve my goals outside that system. Formally having the degree would be nice, but I’m going to keep trying to get what the degree represents through industry research instead.

Although it worked out for me, I can easily see why someone would go back. A few different weightings on each feature would be enough to change the decision.

The common wisdom is that going from industry to PhD is straightforward after 1 year, and exponentially less likely afterwards. This is definitely true, but it’s not because your research skills decay that quickly. It’s that bandwagon effects are real. You’re going from an environment where many people are considering PhD programs, to one where most people have no plans to go back to school. You need to be a much weirder person to decide to do a PhD once you get paid and settled into a work routine. I’m not that weird of a person. Well, I mean, I am weird. Just not weird in that way.

Your research skills may not decay, but your professor’s memory of those skills might. Letters of recommendation are a big part of PhD applications, so if you’re on the fence, it’s better to apply first and defer the offers you get if you want to keep your options open. That way, if you do want to go back, your professors can always recycle their previous rec letter if they forgot what you did.

One piece of advice my friend gave me is that undergrads should mentally downweight their enthusiasm for grad school. If they’re very excited about grad school, they should only be moderately excited, and if they’re unsure about it, they probably shouldn’t go. I still agree with this, but I probably would have gotten more enthusiastic about research if I had gone to grad school. This is not normal. Even if I think doing a PhD would have worked out for me, I would never recommend using a PhD to figure out your life.

If you can get a full-time offer out of undergrad for a good industry lab, along with a reassurance you’ll get a chance to publish, it’s a compelling offer and I would take it seriously.

Despite all my grad school angst, all the knotted up emotions and trains of thought, time has made it easier to evaluate and feel at ease with the choices I made. So I think the main thing I’d tell myself (or anyone else considering these questions) is that it’s okay to be stressed out, and to take all the time you need. This too shall pass.

Thanks to the many early readers for giving feedback, including: Ethan Caballero, Victoria Dean, Chelsea Finn, Anna Goldie, Shane Gu, Alvin Jin, David Krueger, Bai Li, Maithra Raghu, Rohin Shah, Shaun Singh, Richard Song, Gokul Swamy, Patrick Xia, and Mimee Xu.