Thoughts On ICLR 2018 and ICRA 2018

In the span of just under a month, I attended two conferences, ICLR 2018 and ICRA 2018. The first is a deep learning conference, and the second is a robotics conference. They were pretty different, and I figured it would be neat to compare the two.

ICLR 2018

From the research side, the TL;DR of ICLR was that adversarial learning continues to be a big thing.

The most popular thing in that sphere would be generative adversarial networks. However, I’m casting a wide umbrella here, one that includes adversarial examples and environments with competing agents. Really, any minimax optimization problems of the form \(\min_x \max_y f(x, y)\) counts as adversarial learning to me.

I don’t know if it was actually popular, or if my memory has selective bias, because I have a soft spot for these approaches. They feel powerful. One way to view a GAN is that you are learning a generator by using a learned implicit cost instead of a human defined one. This lets you adapt to the capabilities of your generator and lets you define costs that could be cumbersome to explain by hand.

Sure, this makes your problem more complicated. But if you have strong enough optimization and modeling ability, the implicitly learned cost gives you sharper images than other approaches. And one advantage of replacing parts of your system with learned components is that advances in optimization and modeling ability apply to more aspects of your problem. You are improving both your ability to learn cost functions and your ability to minimize those learned costs. Eventually, there’s a tipping point where it’s worth adding all this machinery.

From a more abstract viewpoint, this touches on the power of expressive, optimizable function families, like neural nets. Minimax optimization is not a new idea. It’s been around for ages. The new thing is that deep learning lets you model and learn complicated cost functions on high-dimensional data. To me, the interesting thing about GANs isn’t the image generation, it’s the proof-of-concept they show on complicated data like images. Nothing about the framework requires you to use image data.

There are other parts of the learning process that could be replaced with learned methods instead of human-defined one, and deep learning may be how we do so. Does it make sense to do so? Well, maybe. The problem is that the more you do this, the harder it becomes to actually make everything learnable. No point making it be turtles all the way down if your turtles become unstable and collapse.

(Source)

There was a recent Quanta article, where Judea Pearl expressed his disappointment that deep learning was just learning correlations and curve fitting, and that this doesn’t cover all of intelligence. I agree with this, but to play devil’s advocate, there’s a chance that if you throw enough super-big neural nets into a big enough vat of optimization soup, you would learn something that looks a lot like causal inference, or whatever else you want to count as intelligence. But now we’re rapidly approaching philosophy land, so I’ll stop here and move on.

From an attendee perspective, I liked having lots of poster sessions. This is the first time I’ve gone to ICLR. My previous ML conference was NIPS, and NIPS just feels ridiculously large. Checking every poster at NIPS doesn’t feel doable. Checking every poster at ICLR felt possible, although whether you’d actually want to do so is questionable.

I also appreciated that corporate recruiting didn’t feel as ridiculous as NIPS. At NIPS, companies were giving out fidget spinners and slinkies, which was unique, but the fact that companies needed to come up with unique swag to stand out felt…strange. At ICLR, the weirdest thing I got was a pair of socks, which was odd but not too outlandish.

Papers I noted to follow-up on later:

- Intrinsic Motivation and Automatic Curricula via Asymmetric Self-Play

- Learning Robust Rewards with Adverserial Inverse Reinforcement Learning

- Policy Optimization by Genetic Distillation

- Measuring the Intrinsic Dimension of Objective Landscapes

- Eigenoption Discovery Through the Deep Successor Representation

- Self-Ensembling for Visual Domain Adaptation

- TD or not TD: Analyzing the Role of Temporal Differencing in Deep Reinforcement Learning

- Online Learning Rate Adaptation with Hypergradient Descent

- DORA The Explorer: Directed Outreaching Reinforcement Action-Selection

- Learning to Multi-Task by Active Sampling

ICRA 2018

ICRA 2018 was my first robotics conference. I wasn’t sure what to expect. I started research as an ML person, and then sort of fell into robotics on the side, so my interests are closer to learning-for-control instead of making-new-robots. My ideal setup is one where I can treat real-world hardware as an abstraction. (Somewhere, a roboticist weeps.)

This plus my spotty understanding of control theory meant that I was unfamiliar with a lot of the topics at the conference. Still, there were plenty of learning papers, and I’m glad I went.

Of the research that I did understand, I was surprised there were so many reinforcement learning papers. It was mildly entertaining to see that almost none of them used purely model-free RL. One thing about ICRA is that your paper has a much, much better chance of getting accepted if it runs on a real-world robot. That forces you to care about data efficiency, which puts a super heavy bias against doing only model-free RL. When I walked around, I kept hearing “We combine model-free reinforcement learning with X”, where X was model-based RL, or learning from human demonstrations, or learning from motion planning, or really anything that could help with the exploration problem.

At a broader level, the conference has a sense of practicality about it. It was still a research conference, and plenty of it was still very speculative, but it also felt like people were okay with narrow, well-targeted solutions. I see this as another consequence of having to use real hardware. You can’t ignore inference time if you need to run your model in real time. You can’t ignore data efficiency if you need to collect it from a real robot. Real hardware does not care about your problems.

(1) It Has To Work.

(2) No matter how hard you push and no matter what the priority, you can’t increase the speed of light.

(RFC 1925)

This surprises a lot of ML people I talk to, but robotics hasn’t fully embraced ML the way that people at NIPS / ICLR / ICML have, in part because ML doesn’t always work. Machine learning is a solution, but it’s not guaranteed to make sense. The impression I got was that only a few people at ICRA actively wanted ML to fail. Everyone else is perfectly okay with using ML, once it proves itself. And in some domains, it has proved itself. Every perception paper I saw used CNNs in one way or another. But significantly fewer people were using deep learning for control, because that’s where things are more uncertain. It was good to hear comments from people who see deep learning as just a fad, even if I don’t agree.

Like ICLR, there were a lot of companies doing recruiting and hosting info booths. Unlike ICLR, these booths were a lot more fun to browse. Most companies brought one of their robots to demo, and robot demonstrations are always fun to watch. It’s certainly more interesting than listening to the standard recruiting spiels.

At last year’s NIPS, I noted that ML company booths were starting to remind me of Berkeley career fairs, in a bad way. Every tech company wants to hire Berkeley new grads, and in my last year, recruiting started to feel like an arms race on who can give out the best swag and best free food. It felt like the goal was to look like the coolest company possible, all without telling you what they’d actually hire you for. And the ML equivalent of this is to host increasingly elaborate parties at fancy bars. Robotics hasn’t gone as far yet. It’s growing, but not with as much hype.

I went to a few workshop talks where people talked about how they were using robotics in the real world, and they were all pretty interesting. Research conferences tend to focusing on discussing research and networking, which makes it easy to forget that research can have clear, immediate economic value. There was a Robots in Agriculture talk about using computer vision to detect weeds and spray weed killer on just the weeds, which sounds like all upside to me. Uses less weed killer, kills fewer crops, slows down growth of herbicide resistance.

Rodney Brooks had a nice talk along similar lines, where he talked about the things needed to turn robotics into a consumer product, using the Roomba as an example. According to him, when designing the Roomba, they started with the price, then then molded all the functionality towards that price. It turns out a couple hundred dollars gives you very little leeway for fancy sensors and hardware, which places tight limits on what you can do in on-device inference.

(His talk also had a rant criticizing HRI research, which seemed out of place, but it was certainly entertaining. For the curious, he complained about people using too much notation to hide simple ideas, large claims that weren’t justified by the sample sizes used in the papers, and researchers blaming humans for irrational behavior when they didn’t match the model’s predictions. I know very little about HRI, so I have no comment.)

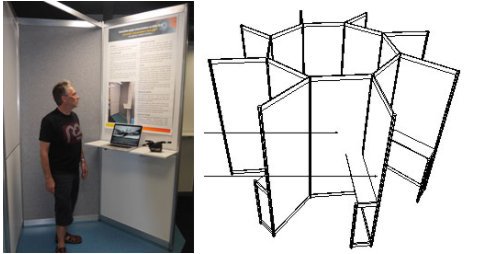

Organization wise, it was really well run. The conference center was right next door to a printing place, so at registration time, the organizers said that if you emailed a PDF by a specific date, they would handle all ordering logistics. All you had to do was pay for your poster online and pick it up at the conference. All presentations were given at presentation pods, each of which came with a whiteboard and a shelf where you could put a laptop to play video (which is really important for robotics work).

(Source)

Papers I noted to follow-up on later:

- Applying Asynchronous Deep Classification Network and Gaming Reinforcement Learning-Based Motion Planner to a Mobile Robot

- OptLayer - Practical Constrained Optimization for Deep Reinforcement Learning in the Real World

- Synthetically Trained Neural Networks for Learning Human-Readable Plans from Real-World Demonstrations

- Semantic Robot Programming for Goal-Directed Manipulation in Cluttered Scenes

- Interactive Perception: Leveraging Action in Perception and Perception in Action