The Blogging Gauntlet: May 6 - State Space Size is a Garbage Metric

This is part of The Blogging Gauntlet of May 2016, where I try to write 500 words every day. See the May 1st post for full details.

When talking about games, and especially when talking about game AIs, it’s very common for people to compare the size of the state space to other big numbers, like the number of atoms in the universe.

But as simple as the rules are, Go is a game of profound complexity. There are 1,000, 000, […] ,000,000,000 possible positions—that’s more than the number of atoms in the universe, and more than a googol times larger than chess. This complexity is what makes Go hard for computers to play, and therefore an irresistible challenge to artificial intelligence (AI) researchers…

Google’s DeepMind artificial intelligence team likes to say that there are more possible Go boards than atoms in the known universe, but that vastly understates the computational problem. There are about \(10^{170}\) board positions in Go, and only \(10^{80}\) atoms in the universe. That means that if there were as many parallel universes as there are atoms in our universe (!), then the total number of atoms in all those universes combined would be close to the possibilities on a single Go board.

The rules are relatively simple: the goal is to gain the most territory by placing and capturing black and white stones on a 19×19 grid. But the average 150-move game contains more possible board configurations — \(10^{170}\) — than there are atoms in the Universe, so it can’t be solved by algorithms that search exhaustively for the best move.

Look, I get it. It’s nice to have analogies for exponentially large numbers because of scope insensitivity. My issue is the conflation of state space size with problem difficulty.

Chess has about \(10^{43}\) positions. Go on a 19 x 19 board has \(10^{170}\) states as said above. So Go is a harder game to play, and look, AlphaGo took a lot longer to make than DeepBlue, it holds up! Checkers has about \(10^{18}\) to \(10^{20}\) states. Backgammon has about \(10^{20}\) states as well. Chinook beat the top Checkers player a few years before Deep Blue vs Kasparov, and TD-Gammon achieved performance close to top Backgammon players in around the same time frame. Looking good for the “number states = difficulty” hypothesis.

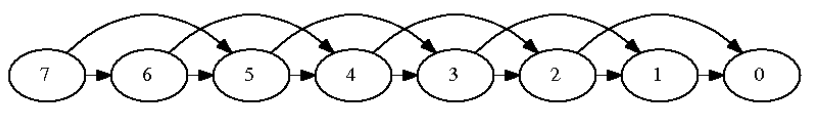

Alright, here’s a trolly counterexample. In the subtraction game, there are \(N\) rocks in a pile. On each player’s turn, they either remove \(1\) rock or \(2\) rocks. The first player who runs out of moves loses.

The game can also be viewed in this way, where each move is following an arrow to another state. Picture by Alan Chang

This game has a very simple optimal strategy. If it’s your turn and the number of rocks is a multiple of \(3\), you lose. If you remove \(1\) rock, the other player removes \(2\). If you remove \(2\) rocks, the other player removes \(1\). No matter what you do, the other player will always be able to force you to start your turn with the number of rocks as a multiple of \(3\). If the pile started at \(9\), it’ll be \(6\) on your next turn, then \(3\), then \(0\)…and now you have no moves and lose.

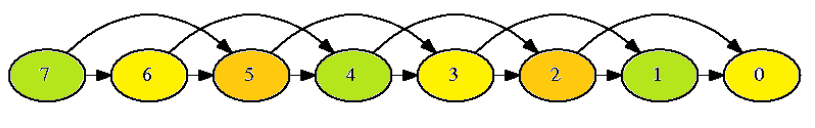

From green states, remove \(1\). From orange states, remove \(2\). From yellow states, it’s a lost game assuming optimal play.

This optimal strategy is one that’s very easy to encode by computer. Yet, we technically have infinitely many states. Every natural number is different from the rest (citation needed), so this game is infinitely difficult, but oh man AIs can solve it, it’s the end of the wooooooooorld.

So obviously it’s not the end of the world. (Yet.) In the subtraction game, we can group states into \(0\) mod \(3\), \(1\) mod \(3\), and \(2\) mod \(3\). (Or by their color in the diagram above, if mod math is scary.) There’s really only \(3\) different states we care about - the actions we perform in each are the same.

What makes a game difficult for an AI is not the raw number of states. It is how well different states of the game generalize to each other, and whether there are nice heuristics that work well on several game states at once. Think of it this way - a computer can explore a billion states in reasonable time. However, \(10^9\) states is a drop in the bucket compared to \(10^{43}\) states. Actually, that metaphor isn’t good enough, so here’s a raw calculation. A liter of water has about \(10^{26}\) water molecules. Seeing \(10^9\) out of \(10^{43}\) states is like having a container of 100,000,000 liters of water, and looking at a single molecule of it.

The only reason Chess is actually a game instead of a pointless exercise is that there is a deep generalization between different game states. That generalization is easy enough to make Chess worth learning to novices, and hard enough to make Chess worth learning to experts.

If Chess has \(10^{120}\) states instead, it wouldn’t really change the problem. The fraction of states you observe are so combinatorially low that it just doesn’t matter.

What made Go harder than Chess wasn’t the number of states. It was because there were no clean heuristics for evaluating board state. You can get surprisingly far in Chess by counting how much material each side has, but Go doesn’t have anything so clear cut. Changing the placement of a single stone can radically alter the value of the board, and it’s very hard to train a computer why that specific stone matters on this specific board.