The Blogging Gauntlet: May 3 - Asynchronous Research and You

This is part of The Blogging Gauntlet of May 2016, where I try to write 500 words every day. See the May 1st post for full details.

Last Sunday, I did Berkeley Mystery Hunt. I can’t talk about the puzzles publicly because this puzzle hunt gets run twice: once during the school year for Berkeley students, and once during the summer for people in the Bay Area.

In every puzzle hunt, I run into the same scenario. A new puzzle comes out, and I take a look at it. I’ll solve it, or I’ll get stuck and move to another puzzle. Either way, I run into a problem. Either I need other people to explain what they’ve figured out, or other people need to understand my progress based on my work so far.

For smaller puzzle hunts, this is fine. Usually you’re all in the same room, so you can ask each other in person. However, when you scale up to massive teams like MIT Mystery Hunt, this becomes a huge concern. They might be sleeping, or be on the other side of the country, and you have to figure out the partial progress from only the notes they’ve written down. If those notes don’t explain the motivation behind all the data collected, they’re practically useless. How am I supposed to know why you removed all the vowels, or where this random column of numbers came from?

I didn’t know what to call this, until I read qntm’s series on antimemetics. If you haven’t read them, I highly, highly recommend checking them out. Start at We Need To Talk About Fifty-Five and follow the links from there.

If you don’t want to, here’s the quick version. Memes are ideas that want to be known, spreading from mind to mind. Antimemes are ideas that want to be forgotten. They are self-censoring. When you stop looking at an antimemetic object, your brain erases your memory and you forget it even exists.

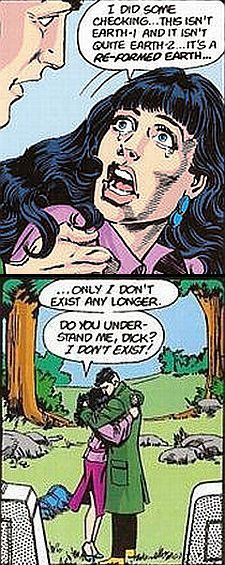

The Antimemetics Division studies antimemes, and they have a devil of a time doing so. It’s hard to study things that everyone rediscovers on a daily basis, and it’s even harder when malicious antimemes erase the lives of coworkers so thoroughly that any evidence of their existence disappears. It’s one of the more horrifying ways to go. You can’t prove your existence to the world if the world doesn’t listen to you…

(from Crisis on Infinite Earths, discovered through TVTropes)

Nightmare fuel aside, there’s a quote about antimemetics research that resonated with me, which is applicable outside the realm of fiction.

Still lost for a logical entry point to the data, Wheeler curses all of her predecessors. Asynchronous research — whereby the research topic is forgotten entirely between iterations, and rediscovered over and over — is a perfectly standard practice in the Antimemetics Division, and her people ought to be better trained than this. There should be an obvious single document to read first which makes sense of the rest. A primer—

(qntm, CASE COLOURLESS GREEN)

The idea of asynchronous research is something I’ve thought about before, but this is the first time I’ve seen someone describe it. And I love the description, it’s perfect.

When I take notes on something, whether it’s for puzzle hunts or lecture, I emphasize writing down motivations, writing down questions people ask about the material, and writing down the answers to those questions. If I don’t follow the lecture, I write what the lecturer is saying anyways, and pepper the margins with question marks to indicate my confusion.

The reason I do this is simple: if I understand the material, I’m not going to read my old notes. In the worlds where I’m reading my notes, I don’t understand what’s going on, so I write my notes towards a more confused version of myself. If my notes spend too long explaining a topic I already get, that’s fine, I’ll just skip ahead. But if my notes don’t explain something in enough detail, I have to struggle through them, and that takes a lot longer.

Understanding something in the now doesn’t mean you’ll remember it in the future, so it’s best to leave notes for your forgetful future selves. Comment your code to explain your awful hack. Mark key ideas to give your future self something to start at, and mark when you’re confused to let your future self know where your notes are dodgy.

If you’re confused about an idea, then get it after a few minutes, write down why you were confused and why it makes sense, because there’s a good chance that if you get confused again, you’ll get confused in the same way. (Writing it down also makes it stick better and decreases the chance you get confused in the first place.)

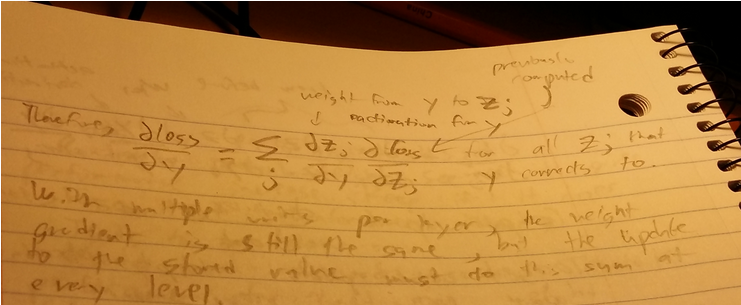

Here are some examples. Below are my notes on backprop from neural nets. I make sure to annotate the intuition behind the gradient.

(Click for full size.)

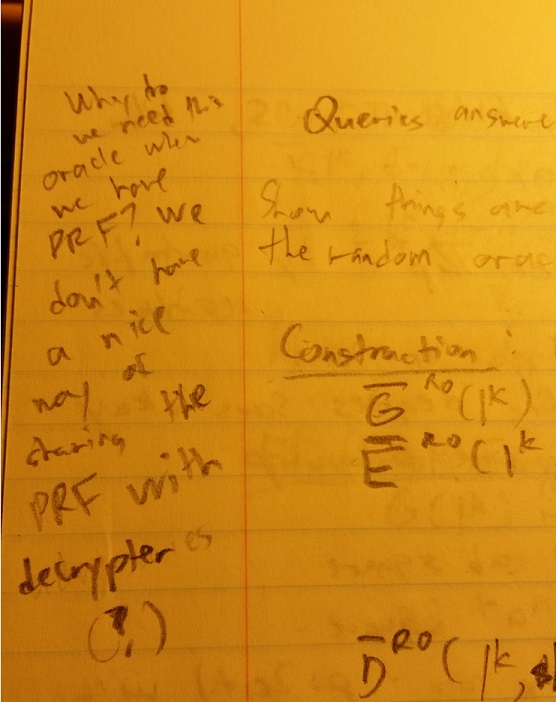

Here’s another example from theoretical crypto. I don’t follow the intuition said in lecture, but I write it down anyways, and note my confusion appropriately.

(Click for full size.)

There are downsides to this approach. I’ve filled notebooks with notes that I’ve never read again, and it’s tricky to take detailed notes while keeping up with lecture. However, I overall think it’s worth it. This may not be the best way to take notes, but it’s what my note taking strategy evolved into. So far, it’s been working for me.